He has visited every county in the United States (there are 3,007).

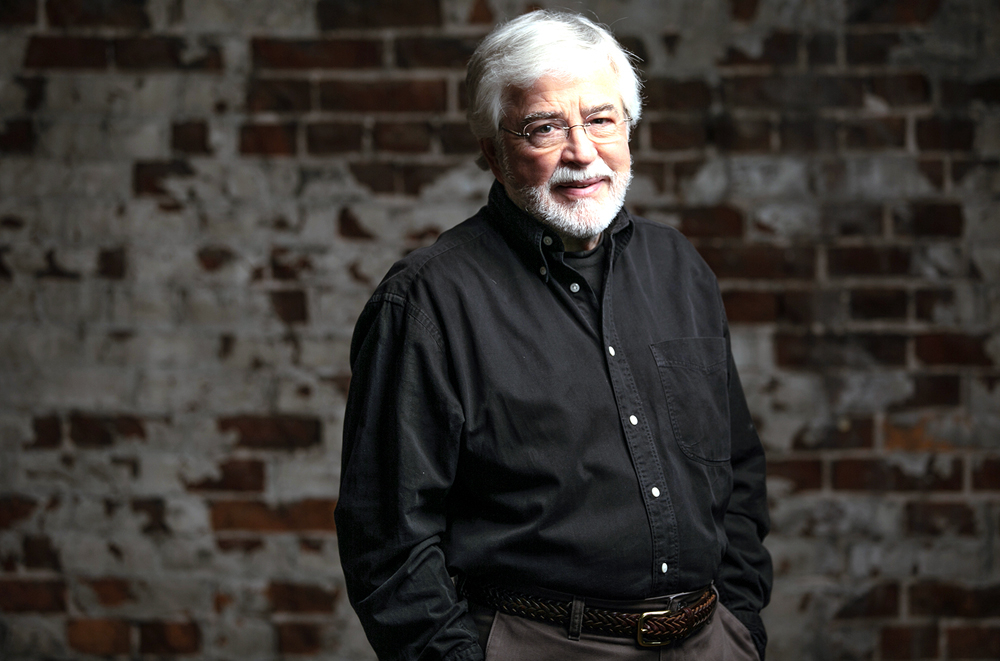

A lifetime spent taking the road less traveled and chatting up strangers has bestowed upon author William Least Heat-Moon, 80, a deep, direct knowledge of the American landscape and psyche.

Heat-Moon’s first three books, all New York Times bestsellers, are American travel masterpieces: Blue Highways chronicles a solo 13,000-mile backroads journey in a van called “Ghost Dancing.” PrairyErth is a meditative “deep map” of the geology, history and humans that shaped a single county in the Kansas Flint Hills. River Horse is an epic account of a four-month voyage across the United States from the Atlantic to the Pacific by boat.

Other books by Heat-Moon include the travel accounts Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey and Here, There, Elsewhere: Stories from the Road and his first work of fiction, Celestial Mechanics, which has been described as a “Blue Highways of the mind.”

Heat-Moon’s writings enjoy a wide following in Europe, where he may be the second most famous Missouri author after Mark Twain.

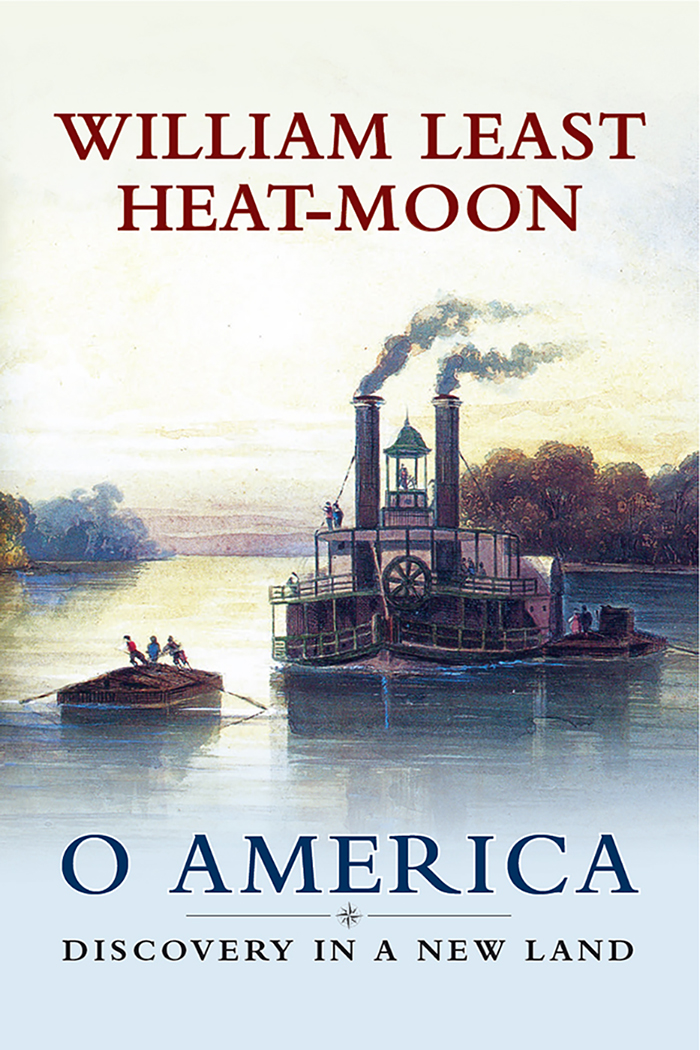

His latest book, O America (University of Missouri Press), released on Valentine’s Day, is at once a love letter and a warning to a nation locked in an eternal tussle between its noblest and basest instincts. The novel, set in 1848, follows a British physician and an escaped slave making their way from Baltimore to the wild backcountry, encountering adventure and memorable characters that provide insights into the ongoing American experiment in democracy.

Born and raised in Kansas City, Heat-Moon now lives on 52 acres near the Missouri River outside Columbia, MO. During a lunch meeting at the Tiger Hotel in Columbia, the soft-spoken, silver-haired author, who is of English, Irish and Osage ancestry, breaks off mid-sentence when a server appears. Turning his body to face her, he casts out a series of biographical questions and listens to the answers with cat-like attention. There is no small talk with Heat-Moon. Things matter.

When our interview resumes by phone on a snowy day, there is ground to be covered before we can embark on the business of the call: snowfall totals at our homes some 250 miles apart, the whereabouts of a mutual acquaintance. He asks for a brief history of my parents and delights in finding details that connect their lives with his own. He once said he set out on his Blue Highways adventure “to meet the nation,” a quest that continues to animate him.

What was your childhood like in Kansas City?

I was born in 1939, and three days after I was born, World War II started. I remember going to the movie theaters in Brookside and Waldo and seeing newsreel footage from the war. They would play them before the cartoons. That was a lot for a kid 4 or 5 years old to take in. For a while I thought somehow my birth had caused the war, but when I got a little older I realized, of course, that was not the case.

We lived about ten miles from downtown, on 74th Street between Paseo and Troost, and we could get to town in less than half an hour on the streetcars, so I felt very much connected to not only the city but to my neighborhood and the adjoining neighborhoods.

Kansas City was a great place for a boy to grow up. Everything you needed was within walking distance. There was a drugstore on Troost Avenue with a soda fountain, so it became a place of major socializing. I remember looking out the big glass windows at Troost, which was also Highway 71, and I knew from my family’s vacations that Highway 71 ran all the way to the Canadian border and almost to the Gulf of Mexico in the South. And I would sit there and think, ‘I want to follow that highway all the way to the north and the south,’ which I eventually did.

Kansas City, for a man who’s interested in American topography, it was an ideal place to be. Every spot was within a couple of days’ drive, maybe a little more before the interstates. San Francisco, New York City, New Orleans—they weren’t far away. I just felt connected to the country being centrally located like that.

Why did you decide to settle down on a former tobacco farm?

Rural life suits me. I’ve let the original tobacco fields grow wild and have been planting a variety of trees, so it’s kind of like a young forest. I figure if I can trade tobacco for forest, that’s a worthwhile thing.

Do you remember the moment the idea for O America lit upon you?

There wasn’t a moment; it was a slowly emerging thing. But around the election of 2016 it was clear that our country was being pushed towards divisiveness, and that the divisiveness was going to be a threat to our democratic way of life.

There was a phrase that was common then, “This is not who we are.” But it is who we are. It is who we have been since the beginning. I wanted to address that.

What do you think is the explanation for this national lack of self-understanding?

Part of the problem is, so many Americans are unaware of our history. I’m not a historian, I’m a storyteller. But the stories that I know from talking to Americans, and the history that I’ve read, they fit together.

I thought what I could do as a writer—maybe—is to try to tell a story that would reveal the historical nature of what it is to be an American living our version of democracy.

How did you tackle the research needed to recreate 1848?

I have about 3,000 books that are entirely within the subject matter of American travel and exploration. So I read travel accounts from 1848 and thereabout. And I listened. It was almost like interviewing people; I couldn’t ask questions but I could hear the answers.

I intentionally set the story before the Civil War, because that complicates everything. 1848 was a little simpler.

I made almost nothing up in O America except for the two protagonists. Almost everything that happens to the protagonists is taken out of a historical account.

Most people understand that violence and racism have plagued us since the beginning, but O America reveals that contemporary problems such as the opioid crisis, income disparity, and the rise of corporations have existed just as long.

Yes, and it’s nothing I invented. People in 1848 were talking about opioids—my protagonist Dr. Trennant carries laudanum in his bag, as people did then. Laudanum is an opiate, a necessary one to keep people from suffering more than they needed to.

And it was also sold irresponsibly, as an unlabeled ingredient in non-prescription tonics and elixirs.

Yes, and today we’re dealing with opioids again. And with income disparity again. Almost all the ills we see today were present in 1848.

O America, beyond its political undercurrent, is an adventure tale full of humor and richly drawn minor characters. It has been compared to Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, and to me it calls to mind Homer’s The Odyssey, the Lewis & Clark journals, and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Were you intentionally paying homage to any of those authors or works?

I have read all of those people, and I would say all of them had some influence on me. But it wasn’t consciously there. The first time I heard a comparison to Huckleberry Finn, I thought, “Of course!” A black man and a white man traveling around together. And I’m sure that, because I had read that book, that helped propel my narrative along in some way, even though I wasn’t conscious of it at the time

The book has not exactly a happy ending, but a glimpse of a possible happy ending. There’s a wonderful sentence on the last page, as the protagonist is waiting for the steamship that is going to carry him to St. Louis to reunite him with his beloved: “Well, well, well. ‘American Democracy’ is in sight, coming forward in a flurry of steam and wood smoke and frantic whistle-blowing to urge us aboard with dispatch.”

“…. today we’re dealing with opioids again. And with income disparity again. Almost all the ills we see today were present in 1848.”

At this moment in 2020, do you think American democracy is going to make it? Are we going to be able to get onboard quick enough?

I wish I could give a definitive answer. It’s a question I ask every day now. I tend to be an optimist, a very cautious optimist. My guess is that we’re going to solve the current political problem. [Pause] I think we are.

Interview condensed and minimally edited for clarity.