As Kansas City and communities around the United States grapple with ongoing racial inequality, we speak with three Black chefs and food business owners about their experiences in the industry.

Fannie Gibson

Fannie’s West African Cuisine

Fannie Gibson learned to cook as a child growing up in Liberia, but she didn’t have any professional training when she decided to share West African food with Kansas City at her own restaurant. She was even warned against the idea by others in KC’s restaurant world.

“A lot of them said, ‘No—nobody wants West African food. The only food that’s accepted is Ethiopian and Jamaican, so I don’t think you should do that. Don’t go that route. Nobody’s going to buy from you. Don’t waste all your money and your time,’” Gibson recalls. “And I’m so grateful I didn’t listen to them.”

After moving from Liberia to Ghana and then Kansas City, Gibson found her new home’s dining landscape without a restaurant serving the dishes she loved to cook at home. She started posting pictures of her creations to social media and quickly found a following. Gibson also learned there was a demand for her food—people asked her to ship dishes so they could experience them.

“I didn’t even have money, I had nothing—I just had the passion and I wanted to bring my food to Kansas City, my culture to Kansas City, and introduce people to West African food.”

“I didn’t even have money, I had nothing—I just had the passion and I wanted to bring my food to Kansas City, my culture to Kansas City, and introduce people to West African food,” Gibson says.

Nowadays, people come from all over the region to try the dishes at Fannie’s West African Cuisine, the Hyde Park restaurant she opened with her husband in 2018. The menu is extensive because Gibson wanted to honor the culinary traditions of all the countries that make up West Africa.

“Our menu does not look like any menu in America,” Gibson says. Offerings include jollof rice—a flavorful staple dish that features rice cooked with tomatoes—sweet and spicy peanut butter soup, and fufu, a starch-based dish that calls to mind a dumpling. Fannie’s also highlights a variety of whole baked fish and stews, including one of Gibson’s personal favorites, cassava leaf.

Gibson says she’s grateful the Kansas City community—one critics told her wasn’t diverse enough to support a West African restaurant—has embraced the food she serves.

“I see the support,” she says. “People from everywhere, all walks of life, Black, white—everybody comes.”

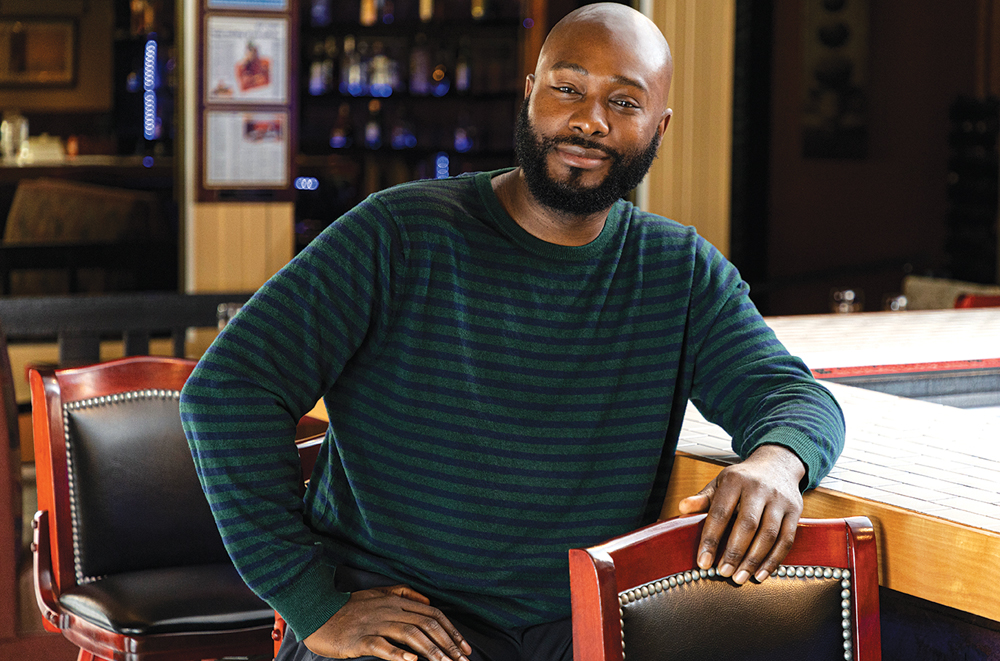

Cherven Desauguste

Mesob

“I’ve always known that I wanted to open my own restaurant, some way, somehow,” says Cherven Desauguste. “But I never thought that it would be this fast.”

What Desauguste, the chef/co-owner of Mesob, calls fast actually came after more than 15 years working in restaurants. After getting his start in South Florida in the mid-1990s, Desauguste moved to Kansas City and worked in a variety of kitchens, including a number of hotel restaurants.

His experience advancing through the culinary world will sound all too familiar to many: As the only Black chef during his time cooking at Argosy Casino, Desauguste says, “I had to make myself noticed. I had to do more, in a sense, than the rest of the guys. It didn’t matter if they were mediocre—it was irrelevant. But as for me, I had to do more. I had to show who I am.”

Desauguste didn’t mind working harder, he says, because he was looking to the future. For him, that vision came to fruition when he and partner Mehret Tesfamariam opened their Caribbean and Ethiopian concept in 2011 under the name Mesob Pikliz. The latest iteration of the restaurant calls Midtown home and is known just as Mesob, but it still serves the two very different cuisines under one roof, respecting their distinct traditions rather than attempting to fuse them together.

The Caribbean side of the menu allows Haitian-native Desauguste to showcase the island-style approach to food, which is focused on fresh herbs, fish, and vegetables.

“We don’t tend to use a lot of heavy spices on our food—it’s all about the marination,” he explains. The Caribbean menu includes dishes such as jerk chicken and waffles with a hibiscus barbancourt rum maple glaze, seafood-studded paella, and pan-fried snapper with fried plantain.

“There are plenty of Black chefs in Kansas City, but most of the chefs that you hear about, it’s all white chefs. We, as Black chefs, are under the radar.”

Tesfamariam’s Ethiopian heritage inspired the other half of Mesob’s menu. But Desauguste admits he started out with little knowledge about the country’s cuisine, which he considers almost the opposite of his own, especially in its emphasis on spices. The Ethiopian offerings include dishes such as tibs, with lamb, beef, chicken, shrimp, salmon, or mushrooms sautéed in a house blend of spices, clarified herb butter, onions, garlic, tomatoes, and jalapeños.

Diners have proven dedicated to the continent-spanning food and helped raise the restaurant’s profile over the years, but Desauguste says many Black chefs receive little recognition from their companies or the public.

“There are plenty of Black chefs in Kansas City, but most of the chefs that you hear about, it’s all white chefs,” he says, pointing out that many smaller businesses don’t have the capital to invest in marketing. Social media is helping to change that but gaining recognition can still be an uphill battle.

“We, as Black chefs, are under the radar.”

Shanita McAfee-Bryant

The Prospect

Early in her culinary career, chef Shanita McAfee-Bryant realized she needed to take a break.

“It wasn’t that I wasn’t passionate about cooking—I wasn’t really passionate about the current industry setup,” she explains. “In the early 2000s, late 90s, it was hard to be a woman, especially a Black woman.”

Women were often relegated to making salads and desserts, and as a Black woman, she experienced blatant racism in addition to the sense she had to work twice as hard as her colleagues.

“I didn’t feel like I ever had the luxury of being able to step back and take a little bit of time for my personal life,” she says. “I’m like, ‘I’ve got to keep working, I’ve got to be at work, I’ve got to be in the restaurant, I have to be there, people have to see me.’ You feel like you just have to do, do, do, do, do.”

After more than 20 years working in Kansas City’s culinary industry, chef Shanita McAfee-Bryant has a wealth of experience. She attended culinary school at Johnson County Community College, and cooked at YaYa’s Euro Bistro, The Westin, Rockhill Tennis Club and the Kansas City Club in addition to previously owning her own Southern-inspired restaurant and food truck, Magnolias.

Although she still offers limited catering, McAfee-Bryant’s focus has now shifted to advocacy with the creation of her nonprofit. The Prospect will offer culinary and entrepreneurship programming for under-resourced communities as well as provide healthy food. USDA produce boxes are currently distributed on Thursdays and Fridays.

“I do feel like I’m in a space where I’m maybe breaking barriers and kicking down doors so that for somebody coming up behind me, it’s going to be a little bit easier for them.”

McAfee-Bryant also created a platform for Black chefs to discuss their experiences with “The Conversation,” a Facebook Live show that she co-hosts with acclaimed pastry chef Erika Dupreé Cline. The series was inspired by conversations McAfee-Bryant had with friends that she didn’t see happening in more public settings. Topics covered since “The Conversation” launched earlier this summer include self-care, mental health, the value of culinary school for people of color and how the media ignores Black chefs.

“It’s really hard to be ‘the only’ because you second guess yourself all the time,” she explains. “Did they write that article about me because it’s February and I’m the only female Black chef in Kansas City, or did they write that article because they genuinely cared about my perspective and my career and my experience?”

Despite all her experiences, McAfee-Bryant has no plans to switch careers.

“Food is still my outlet,” she says. “I’m never going to turn my back on food—never. It’s never going to get too difficult where I don’t want to do it. I do feel like I’m in a space where I’m maybe breaking barriers and kicking down doors so that for somebody coming up behind me, it’s going to be a little bit easier for them.”