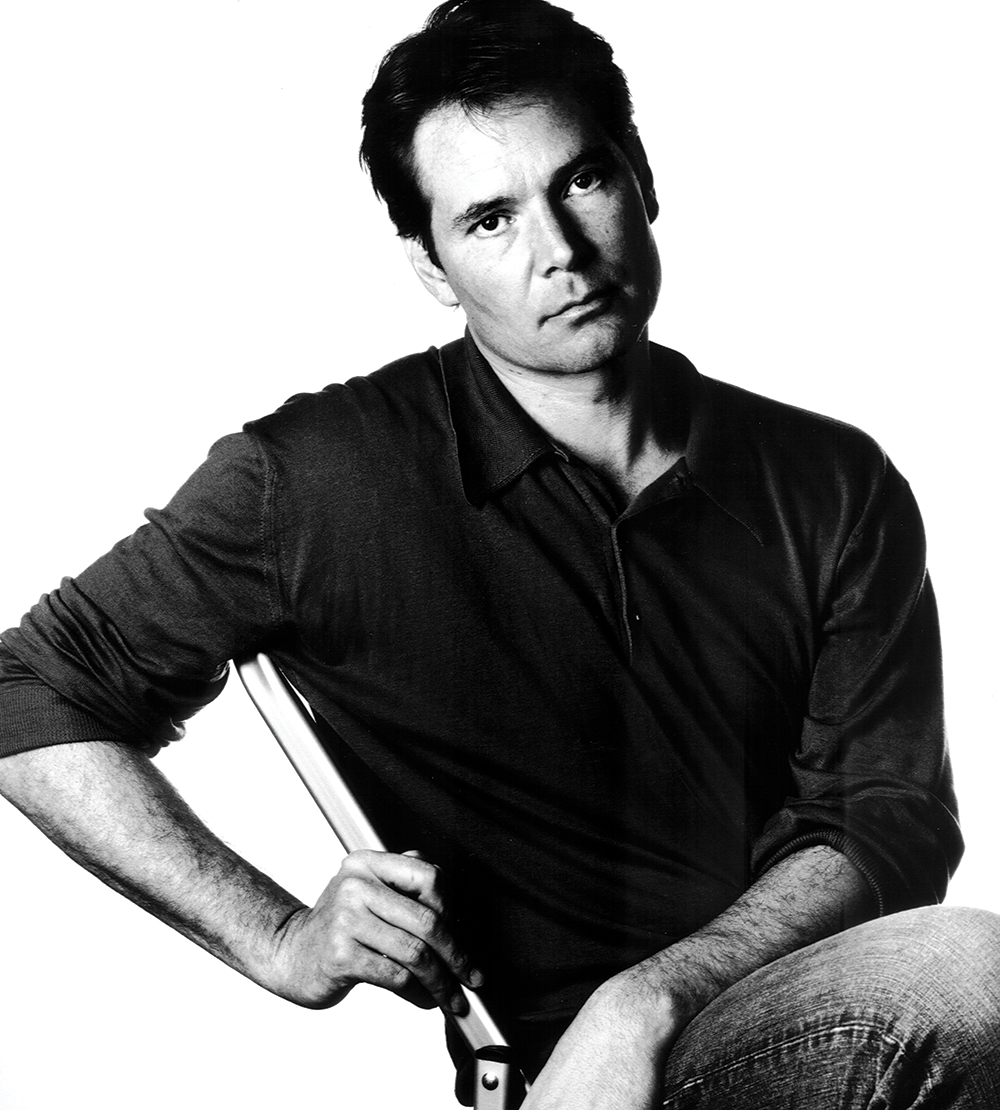

Internationally celebrated dancer and choreographer David Parsons thrilled his first audience as a teen with a gravity-defying exit from a trampoline at an arts camp show in Kansas City. His career has been soaring ever since.

Parsons, 61, began training with the Missouri Dance Theater at age 14. At 17, he moved to New York when he was offered an internship at the Ailey School. In 1978 he joined the Paul Taylor Dance Company as an apprentice, then became a principal dancer. Taylor created roles showcasing Parsons’s athleticism.

He performed as a guest artist with New York City Ballet, toured with MOMIX and performed with Mikhail Baryshnikov’s White Oak Dance Project.

In 1985, he founded Parsons Dance. The company has performed in at least 445 cities in 30 countries on five continents. Parsons has also choreographed Broadway productions and performances in the fashion industry for Loro Piana and Missoni.

Last year, Parsons choreographed A Play for Love for the Kansas City Ballet. A Parsons Dance performance with the Harriman Jewell Series at Muriel Kauffman Theatre has been rescheduled for September 9, 2021.

Parsons spoke with IN Kansas City by phone during a break while building shelves in the garage of the Stamford, Connecticut, home he shares with his partner, Melinda Cloobeck.

What was your childhood in Kansas City like?

In the beginning it was great. We lived in Armour Hills. It was an incredibly beautiful neighborhood—middle class. I went to JC Nichols School. And then when I was 11 or 12, my brothers and my father left my mother, and I had to stay with her. She went into a terrible mental state; she really had a breakdown. I stayed with my mother in that house until I was 17 and one of my brothers came back. I said, “Are you gonna stay with mom?” And he said yes. Three days later, with $70 in my pocket, I got on the train to New York City and never went back.

My mother and my family are fine now. It was difficult to see her go through that and to have that family break up on me. Then I found another family in Missouri Dance Theater, and when I moved to New York I found another family, the Paul Taylor Dance Company.

The other thing about Kansas City that was formative, was, at the age of 15, I had a motorcycle accident with the mayor of Kansas City’s daughter on the back. There was a photograph on the front page of The Kansas City Star of me on the ground with my dog licking me, because he was the one that made us wreck, and Nina on a stretcher. And the caption said, “Nina Wheeler and the boy…” From then on, I always wanted to make sure my name was better represented. [Laughs]

Nina and I are still close and the last time I performed at the Kauffman, [former mayor] Charlie Wheeler came.

When did you become aware of dance as a child?

We had a trampoline in the backyard. I was a gymnast and a trampolinist. I was making pieces on the trampoline at age 12 or 13. I made my first piece to Led Zeppelin.

Do you remember the song?

Kashmir.

What did that look like, trampoline choreography?

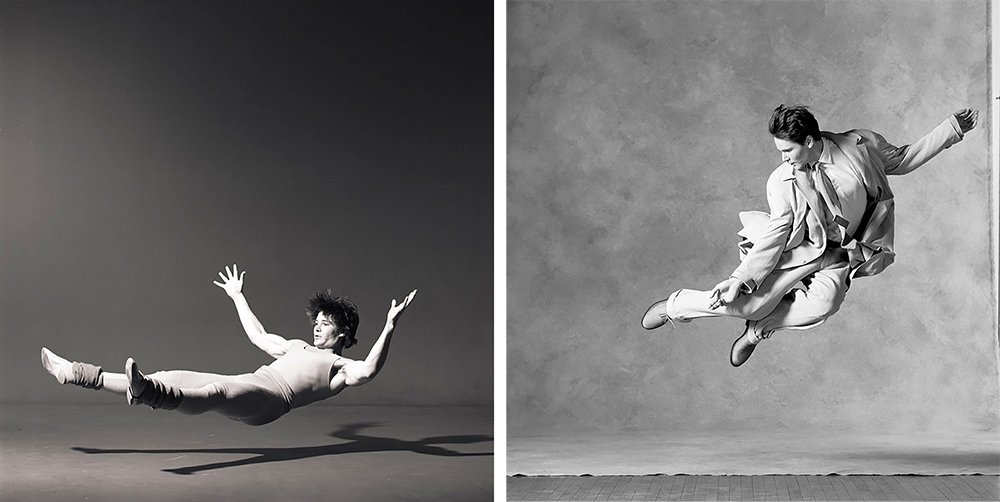

Well, you’re in the air all the time. And it stuck. We’re known as a company that has a lot of air time.

Do you remember the point when dance started to feel like a vacation?

Yes. My mom put me in arts camp at Sunset Hill School. There was a show that I was in, and I put my trampoline on the stage. At the end of the piece I grabbed onto the pipes above, after my biggest bounce, and I pulled my legs up and never came down.

Holy. Cow.

[Laughs] So basically, I exited up. The curtain closed. The audience went crazy, and at that moment I knew I wanted to be in show business.

Perhaps your most famous piece is Caught, a solo where a strobe flashes repeatedly as a dancer leaps, making it appear the dancer is walking on air. Where did you come up with that idea?

I was working with a photographer named Lois Greenfield—I’ve had a relationship with her for 35 years—she made her name shooting dance. We would go in the studio and just play, and I realized that there was a way I could use a strobe light to catch a dancer on a dark stage and it would seem like they never hit the ground. We all have dreams of flying, that connects us as humans around the world. It’s a jaw dropper. You can hear the audience gasp when you’re dancing it.

What were the early days like as a young kid from the Midwest in New York City?

Two weeks after I arrived in New York, the 1977 blackout happened. I was staying in an apartment for $130 a month. I used to work the graveyard shift, 11 to 7, pumping gas on 90th Street and Third Avenue. During the day, I had a scholarship with Ailey, and I would sleep at two times during the day.

After eight months in New York, I got into Paul Taylor as an understudy, and six months later, I was touring the Soviet Union with the Taylor company.

You give Paul Taylor credit for teaching you to treat dancers fairly. What do you mean by that?

I am in the contemporary world. Ballet is a different world. Sometimes you have 100 people in a ballet company. There are only eight people in our company, and they are all principals. We have understudies behind them, but they don’t go out on the road.

To have good dancers you need to pay them. They need to live like everyone else. For 35 years we’ve had medical coverage for free. That is how you build trust.

It’s a very small group and I like it that way. You’re working so closely; you are more like friends. You’re not going to mess with your friends, because you don’t want your friends to leave you. We look for people that want to spend their whole career with us, and most dancers do, because they tour the world and they get to do other people’s works.

When I was in Paul Taylor’s company, one of the reasons why I left after nine years was because he didn’t do anybody else’s works. I wanted to do other works.

Does your company have a personality?

We are known as a very physical company. In my opinion, it’s a very vital company. We’re constantly looking for ways to keep ourselves alive and moving in different directions. Thirty-five years is a long time to have a not-for-profit organization.

“Nowadays, it’s more acceptable to be accessible. Times have changed. I don’t care what people think. I’m not going to change who I am. We love to take our audiences on a rollercoaster of emotions.”

Your work is frequently called “accessible.” That can be a hot-button word in all areas of art. In dance, what is considered not accessible, and what makes your work accessible?

Nowadays, it’s more acceptable to be accessible. Times have changed. I don’t care what people think. I’m not going to change who I am. We love to take our audiences on a rollercoaster of emotions. We love to have an audience member laugh. We want to make sure when you leave, you won’t forget Parsons Dance, and I think we achieve that.

In the early stages of your career, AIDS hit the dance world hard. Now Covid is hitting all arts groups hard. How do you view the situation?

It’s amazing I’ve been able to land on my feet when you look at what I’ve lived through. As soon as I arrived in New York, there were the blackouts and riots.

Then, we were in the air over Texas and saw the Space Shuttle break up.

You were looking out the window of a plane at the Challenger when it exploded?

Yes. Then there was the AIDS crisis, and people in Paul Taylor’s company were dying while I was there. And we [Parsons Dance] were in New York on 9/11. We were supposed to perform that night in between the two towers.

When I think about the pandemic, I think about a piece I made called Ring Around the Rosy after I left Paul [Taylor]. It was an epic about the Black Plague over 400 years ago that killed millions of people.

I had been touring in Italy and I stayed at a friend’s apartment in Milan, and I looked down and said, “What is that old beautiful building?” He said, “That was a plague hospital.” So I studied that whole thing and had an original score by Richard Peaslee, and it was so affective.

The same thing is happening today, that kind of fear and not knowing.

How is your company responding to the pandemic?

We had been in Wuhan the year before the pandemic, and we have an employee from there. Her parents let us know [about the virus]. We have also spent a lot of time in Italy and we were hearing from people there. We did our 2020 gala online in May.

Since July, our dancers have been working in pods in three locations. I wanted to do something profound [in response to Covid] to Beethoven or Mozart. The dancers didn’t want to do something Covid-related. They wanted to do something about communication between humans in the age of social media and cell phones and computers.

My lady’s son, David Cloobeck, is a composer. He studies at Berklee College of Music in Boston. So David did the music, working at night. He put together a beautiful score that reminds us of the sounds we hear every day, little bleeps and tones like you hear on your phone. The piece is called Side Effects. We performed it on a farm in Stamford, Connecticut, to 100 close patrons and board members. It really struck home with people. Now they’re working on a new piece. We’re producing like crazy.

Compared to opera or ballet, my world is very enclosed. The only thing that’s going to affect us is touring. At the age of 61, all I do is keep my paints, which are my dancers, together so I can create and give my dancers work. We will survive and do what we do on my small level. We’re agile.

I started my company with Howell Binkley. He’s lit every one of my works and he was my best friend. Unfortunately, he passed away in August from cancer, so we are reeling a little bit. He was my best collaborator. He did a little show called Hamilton and picked up a Tony for it. [Chuckles] He was huge. So I’ve got a real hole in my heart not having that guy around. It’s unusual to form a dance company with a lighting designer as a partner, but we had a beautiful run.

Your mission statement reads, in part, “We envision a more positive, creative, and welcoming world.” How can dance make the world better?

Oh. Oh. Dance is just inspiring to see. It fills you with hope. It fills you with positive energy to see someone really express themselves in a nonverbal way. It can go into your soul. I never underestimate the power of good dance.

Interview condensed and minimally edited for clarity.