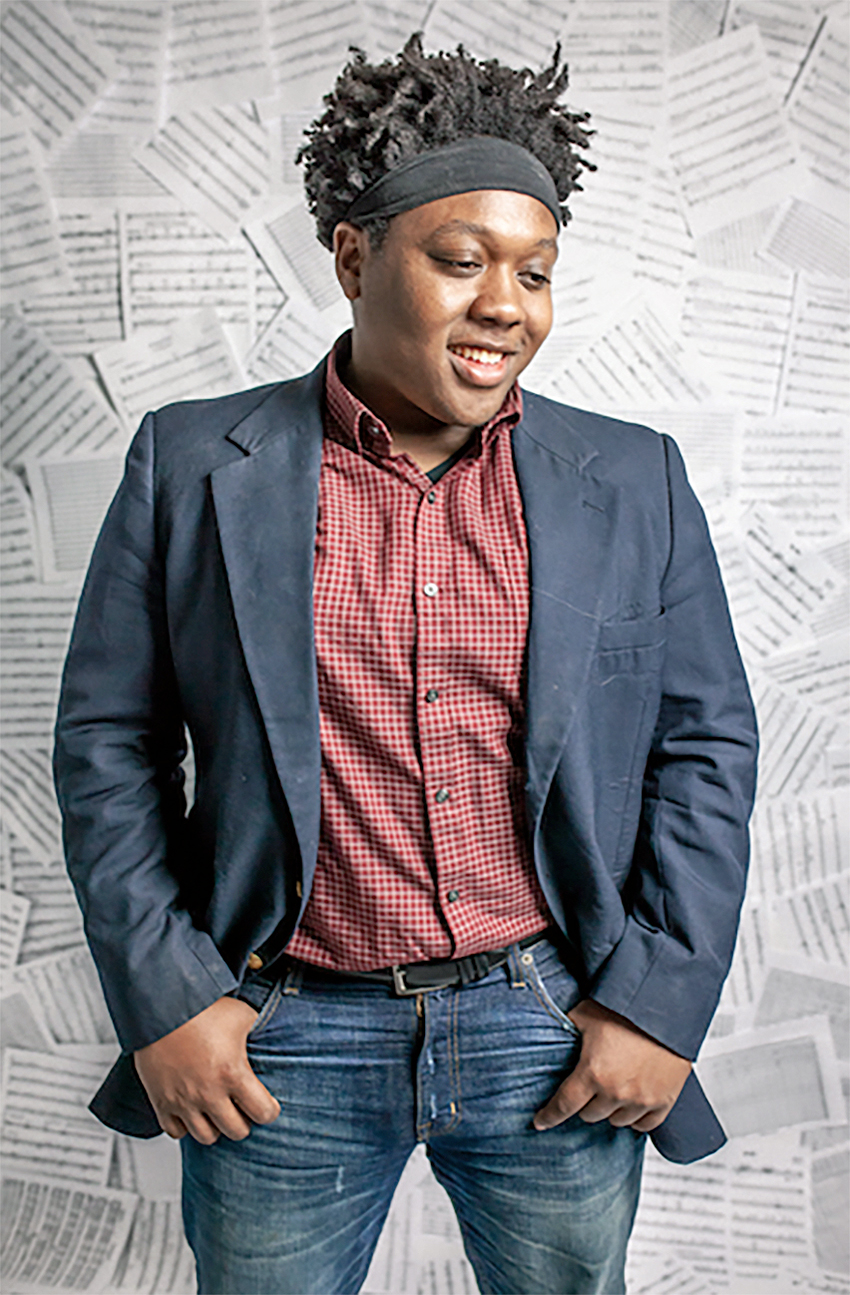

After moving to Kansas City in 2013, Ryan Davis immersed himself in the city’s music scene with much ambition and enthusiasm. His hard work and talent have paid off, abundantly.

Davis plays trombone and raps in The Phantastics, a nine-piece hip-hop/funk/jazz/soul ensemble; he plays trombone in Brass and Boujee, a groovy hip-hop/jazz orchestra; and he fronts The Deshtet, a jazz ensemble he launched in March.

But most conspicuously, Davis performs as Kadesh Flow, a multi-faceted and multi-instrumental hip-hop artist whose “nerdcore” raps address his favorite interests, like anime, video games, and other facets of geek culture.

Davis recently answered questions from In Kansas City about his Southern upbringing, the Nerdy People of Color Collective, and a bucket-list performance on a bill with Janelle Monae.

You grew up not far from Gulf Shores, Ala. What was your childhood like?

I grew up in the woods. Working-class family, highly fundamentalist, Apostolic, Christian upbringing. Loving but tough-love sort of family.

By some zoning miracle I ended up in a school that was predominantly upper-middle class. I say “miracle” because a number of my relatives ended up at different schools and didn’t get to see or be normalized to what I saw, which was doctors, lawyers, entrepreneurs on a regular basis in my classmates’ parents.

A number of people in my family didn’t view high success levels as something that was normal, and getting to see those on my end really helped me out, mostly because I was granted access to things that a lot of young black kids don’t get in lower Alabama.

When did music first become important to you?

My parents convinced me that I was brilliant when I was a toddler (the accuracy of their sentiment is still up for debate), and the confidence they instilled in me was reinforced by the fact that they made sure that I was placed in enriching academic environments.

My dad tried to raise me to be competitive athletically. Both sides of my family practically spit out collegiate football talent, so this made sense. It didn’t necessarily work the way he intended, though. I was competitive academically, and then musically. I competed with my friends for grades. Then, in high school, I had a moment where I didn’t want anyone to be better than me at anything I actually took seriously.

After that, I started making all-state honor bands, placing in poetry competitions. Alarmingly, I was also learning that a number of my white friends and their parents viewed me more as an exception to the “rule” relative to their views on black Americans as compared to just viewing me as an upwardly mobile person. This shaped a lot of my time in college, as I shifted from being more of a conservative, respectability-minded youth to a more progressive musician and student.

What bands or music artists first inspired you to pursue music seriously?

J.J. Johnson, Bill Watrous, Wycliffe Gordon, Dave Steinmeier—all trombonists. I wanted to be the next Wycliffe for a while.

College saw me become immensely more passionate about hip-hop. I was listening to a lot of Lupe Fiasco and Tech N9ne—yes, in Alabama. I find it incredibly ironic that I ended up in Kansas City.

In graduate school I started listening to a former teacher … rapping about video games. He performed as Mega Ran. I had been writing video-game and anime rhymes for years and basically not telling anyone, so finding out about him and seeing him build a career out of that changed my life. I began uploading my content to YouTube not long after.

Ran is like a big brother/mentor now. I’ve encountered Tech from time to time, even grabbed advice from him at a couple of shows and got to know a number of artists on the Strange Music roster, record trombone cuts on a few songs, rock a few shows, etc.

How did you end up in Kansas City?

Cerner Corporation hired me out of grad school. I then fell in love with Kansas City. Didn’t take long for that to happen, either.

You have performed at a few MAGFests, a music and gaming festival. Talk about that community and how it has helped your music prosper.

In a nutshell, the Nerdcore and VGM (video game music) communities are what made me start taking music seriously. I’d rapped at a high level for a while, but I didn’t want to be in hip-hop initially. I thought there was no place for me in it. Learning that there were niche communities that would love my tastes in content changed the game for me.

MAGFest, specifically, is the dream festival for a number of video-game music enthusiasts. I thought in college that if I got to play MAGFest, ever, that moment would be the moment I really start making moves. It’s important because, in a lot of ways, it is a gigantic family reunion for fans of video games and video-game music. However, it’s unique in that it fully commits to being both a music festival for VGM and a video-game industry convention all at once.

You have also been active in the Nerdy People of Color Collective. Talk about its origins, how it has evolved, and why it’s important.

This may need to be a separate conversation, as there’s so much to discuss here. The Nerdy People of Color (NPC) Collective is a group of creatives and influencers who advocate for representation of marginalized groups in nerd and geek spaces. Said spaces have been traditionally CIS white-male dominated. It was started when Mega Ran discovered many of us (mostly dope, nerd-influenced rappers) online, or became friends with us or toured with us, one way or another.

It’s evolved in both reach and scope. It was initially just rappers and a wrestler (WWE star Xavier Woods). Now, while the core group is still mostly rappers, it also includes a network of influencers from marginalized groups, such as visual artists and designers, DJs, programmers, podcasters, authors.

We also went from being a group of unknowns to a potent group that the biggest anime, video game, and pop culture conventions in the U.S. want to book as main stage shows or main events.

There is a massive intersection between hip-hop culture, anime culture, and video-game culture. A number of conventions weren’t addressing this intersection, and when the NPC began coming in as musical guests, then packing out panel discussion rooms for topics like “Anime and Hip-Hop,” the conversation began to change some.

What’s coming next is completely outrageous. We are partnering with one of the most prominent anime licensors in the U.S. in presenting shows that celebrate Samurai Champloo’s 15th anniversary, as well as the life of Nujabes, a producer who could be considered the Japanes J. Dilla, who created a concept he called “new jazz” which basically became lo-fi hip-hop, and who spearheaded the Samurai Champloo soundtrack.

We’re doing a run of shows at the largest conventions in the U.S. with many of the vocalists with whom Nujabes worked. The first iteration is at Momocon, a massive anime convention in Atlanta, in May.

As part of the Open Spaces festival last year, you performed with Brass and Boujee at Starlight before Janelle Monáe’s headlining set. What was that like?

That was a dream. I don’t know what else to call it. It was immensely validating. People from Janelle’s band were following me on Instagram before the show. Her bassist was telling me how excited she was. It definitely helped that Marcus Lewis, who arranges all the Brass and Boujee music and runs the big band that backs all of the tracks for the project, had played with Janelle for almost a decade. The band knew him and seemed to be curious as to what he was doing next.

Janelle told me that we were amazing and that she appreciated us. Her band was backstage clapping for us when we finished our set. That meant the world.

What is your impression of the Kansas City music community?

Kansas City can stand toe-to-toe with any city on the planet, from a talent perspective. I’m consistently in a state of awe at the people with whom I play and have become friends and with the people who keep just popping up and being outrageously good. It’s like world-class talent just materializes here.

I have a friend who is a prominent music critic who suggested that maybe I shouldn’t go to New York or L.A. out of grad school. Maybe I should graduate to something that is bigger and has a better scene than Tuscaloosa, but is further along than Birmingham (this was in 2013).

I ended up doing exactly what she suggested, and reaping the benefits she thought I’d reap. The Kansas City music community has been good to me. The people are great. It is incredibly supportive. The multi-genre collaborations that are happening here are completely unreal. I absolutely love this music community, and right now I feel that I need it like I need food.