Like most nights this miserable winter, it was cold and it was wet and it was gloomy.

Smartphones across the metro chirped and chimed and blooped and bleated, warning folks to stay home because the roads were going to turn slick any second now.

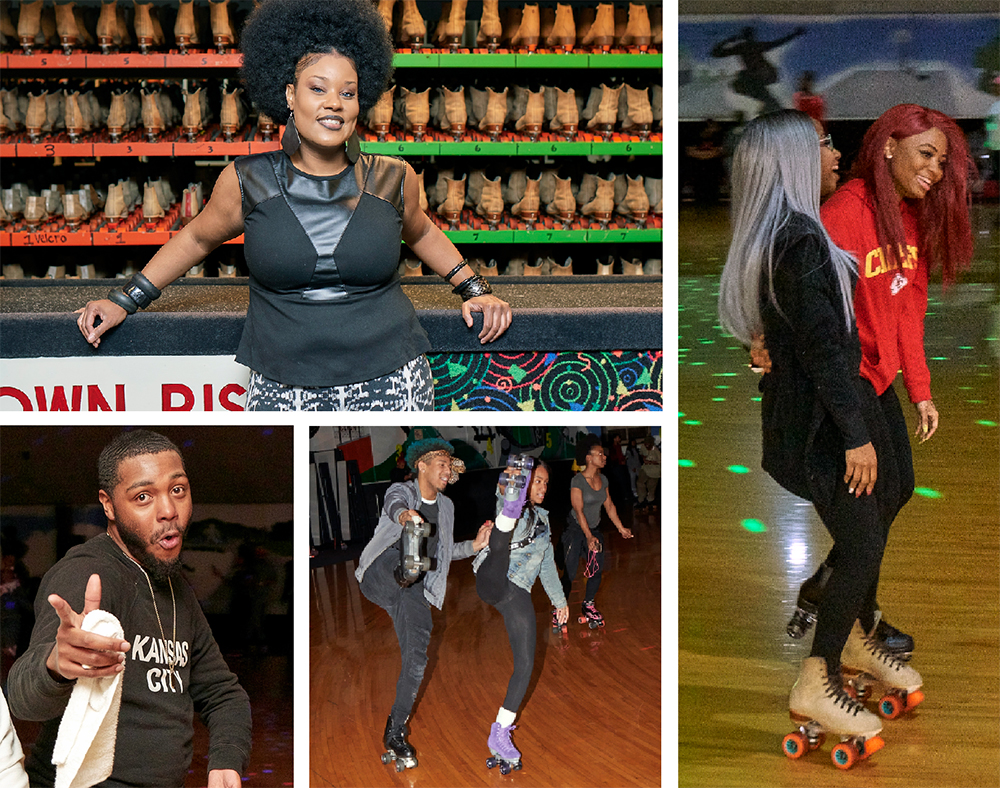

But this was a Sunday night, adult skate night at Winnwood Skate Center. A little weather wasn’t going to stop the people from coming out as they have every week for years—some for decades.

“Sunday nights have always been the night,” says Mike Richardson, a 44-year-old salesman by day and roller skater by night. “Rhythm Lanes, Riverside, Grandview. It’s been huge in the black community since before I was born.”

Those unaware of what’s going on in America’s skate rinks might get ready. United Skates, a documentary airing on HBO, helps bring to light what communities in Kansas City and across the country have known for a very long time: People are rolling.

Richardson performed in the 2005 film Roll/Bounce. At the time, he was part of a squad that skated across the country—Chicago, Atlanta, New York, Detroit. He had skated as a kid, but gave it up and got into breakdancing, pop and lock, beat boy, stuff like that. Then as a teen, he worked at a rink and started putting the two together.

“Honestly, it came kind of easy to me,” he says. “And I just developed my own way of doing things.”

Just in case you may have forgotten what the inside of a skating rink smells like, it’s … pretty much exactly as you remember. Popcorn. Sweat. Sweets. Nacho cheese. Hot dogs. Body heat. Chicken wings.

On adult skate night, though, it takes a minute to realize the nostalgia wafting through the air is missing something.

It sounds different.

Sure, the music isn’t the Beatles, Boston, or Bon Jovi, and the boys are neither Backstreet nor Beastie. That’s not it, though.

The screams. There are no screams.

There’s also no over-the-top laughter. No one is beefing with anyone. There are no inconsolable toddlers; no overreacting adolescents.

It’s just grownups, skating. Hundreds of them rolling around the rink like wind over wheat.

There is music, though. It’s constant, and it comes from everywhere. A heavy bass remix of Bill Withers’ Ain’t No Sunshine (When She’s Gone) pulls people away from the benches and tables. They glide on the one, step on the two; then glide on the three and step on the four.

By the time the chorus hits, the skaters are nearly in sync, like fireflies on a late summer night. All except for one woman, who rolls in reverse while checking her phone and listening to her earbuds, oblivious to the older skaters dodging her and buzzing by.

Rink side, deep laughter breaks out among a group of older men as one of the guys slaps a domino down on the table in frustration. A man near the skate rental counter shakes his head and smiles at the sight of a young couple some 40 years his junior renting those brown suede roller skates ubiquitous in rinks across the country.

He laughs. “People who have brownies don’t roll,” he says.

The man, Ronald Jones, is 61. He’s sporting a pair of black skates with white LED lights strung up the back. He decorated them himself. It’s his thing. Jones has been skating for 45 years, everywhere. He came from a family of 13 and got his start at a combo skating rink/bowling alley off 5th Street in KCK.

“My dad took us, and I saw a little girl skating there,” he says. “She was doing everything, and I thought, ‘If she can do it, I can do it.’ But it took me 10 or 15 years until I really learned how to roll. But that’s OK. Even if you can’t roll, you find someone to help you roll and get better.”

At the far end of the rink, the DJ drops Will Traxx’s Let Me See Some Footwork, and the number of skaters on the floor doubles and triples.

The swirl finds another gear. At the speeds the skaters are traveling in this hurricane of humanity, wipeouts seem inevitable.

Yet there are none.

A man on a certain collision course with a pregnant woman dips his shoulder at the last second and slides to her outside by inches.

A young man about to plow over an older man skating in reverse reaches out his hand and the old guy grabs it. They do-si-do around each other twice, and the elder skater is sling-shotted forward even faster. Later, they said they didn’t know one another, they just did what they do.

A green-haired woman skates in reverse while her adult daughter skates nearly perpendicular to the floor, holding her momma’s ankles.

The mother, Patrice Koonce, is 54. She rolls circles around some of the younger people at the rink. She compares the skating community to Harley riders, going from city to city to roll. Like a lot of the crowd, she started skating at about age 5 or so. She’s seen it come and go in KC.

She’s also seen black skaters discriminated against at different rinks over the years in Kansas City.

Some of the crowd ended up at Winnwood because they were disrespected at another rink, long since closed down. She and others moved the adult session to Winnwood nearly two decades ago because their regular place turned them away.

“What had happened was, they invited some people to skate that weren’t our color and started turning us away,” she says. “We boycotted it. We’ll take our black dollars and put them somewhere else.”

Koonce says sometimes the skating crowd gets an unearned reputation for rowdiness, though there was a time a while ago when kids would come in just to cause trouble. She said Winnwood’s owner, Tom Frisby, nipped that problem by making people keep skates on at all times. It’s tough to tussle on eight wheels.

Frisby, who has owned the Winnwood since 2001, says the great thing about the adult-skate crowd is they police themselves.

“One of the first times we had a late-night session here, I saw the side door open, and I’m wondering what’s going on,” he says. “Then I see a pair of skates get thrown out the door. And then I see a person get thrown out the door, and the door gets shut behind him. Later, I asked one of the regulars what happened, and he said, ‘We ain’t going to let anyone screw up our place.’ So, I’m like, ‘OK’.”

Frisby, 53, once was a skater of all disciplines: art, freestyle, dance, pairs, a little bit of speed skating. His rink is one of seven in the metro. Like any business, the struggle is finding and keeping customers.

“The skating industry as a whole forever and ever and ever has been a roller coaster,” he says. “You grow one group through grade school and middle school and then it becomes uncool so you start all over again.”

Frisby knows from experience. His parents would drive him to his home rink in Lee’s Summit six days a week from the time he was a little boy. His whole competitive career was out there. His teen years brought other interests, though.

“There at the end I came here to Winnwood to skate pairs with a girl, but perfume and gasoline took over,” he says. “I was done.”

Thursday nights bring in the demo derby skaters. Friday is traditionally teens. Saturday is for kids and families and birthday parties. Sunday is for private parties until the adults come in around 10.

It may be the adult crowd, though, that appreciates this place the most. Skater after skater praises the rotunda wood floor, which is Canadian maple laid in an oval with arced corners and no seams. Frisby says a crew re-finishes it once a year.

Those times they’ve had to close down for resurfacing take a toll on the regulars.

“There was a time, they were closed for four weeks, and we didn’t know what to do,” says Rachel Dion, a 39-year-old hairdresser. “I might have gone to the movies or something just to get out the house, but we couldn’t wait until the floor was done so we could get back out there.”

Skating has been a lifelong pastime for Dion. She said she and her sister received skates for Christmas one year when they were very young.

“We started skating in the basement of our house,” she said. “It wasn’t a big basement, but we were small, so it was big to us. This floor here is just smooth from corner to corner. We have one of the best floors.”

David Boaz agreed, and he’s skated a lot of places. Not only is he a member of the all-gender Fountain City Derby squad in town, he skates for Team USA’s Men’s Roller Derby Team. He’s also one of a handful of white skaters among the crowd this Sunday night.

“I’ve never had any trouble being the ‘token white guy’ or whatever,” he says. “Skating is one of those places where everybody comes together.”

His day job is a laboratory supervisor. On the floor, he’s agile and graceful and fast—really fast. Still, even with the tattoos on his leg, it’s hard to imagine him as someone who might truck someone in a derby match. But at 6’2” and 215 pounds, he is a good-sized dude.

“I’ll hit people as hard as they hit me,” he said. “Maybe in the championship, I’ll take it up a level. I try not to be a douchebag.”

The skater stories, they go on and on.

Larry Shipley is 75 years old, and he’s had five bypasses. He skates every week, which is probably why his doctors told him he had the body of a 40-year-old man.

A 59-year-old guy who called himself “Skatemaster” said the dizziness he experiences as part of his disability from his time in the service just disappears when he’s on skates.

C.J. Walker, a 23-year-old local guitarist, laughs when one of the older guys says, “These young guns just want what we got.”

“That’s true, that’s true,” Walker says. “We’re trying to keep up with them. They’re the ones who started it.”

Kenneth Walker, 57, shows off the scar tissue he has all down his arms and legs from a nasty bike-racing wreck years ago that also tore his Achilles. The upside is the accident brought him back to skating, which he gave up for bicycling. In the summer, you’ll see him skating outdoors at Swope Park. He says he’s not the skater he used to be, but he comes to Winnwood for the community.

“A couple of weeks ago, a friend, he’s a longtime regular out here, he broke his leg,” Walker says. “And everybody surrounded him, trying to calm him down and make him feel better, even after the session was over. It’s that kind of community.”

Some of the old ones are trying to bring along the younger ones, too. Byron Egan, 55, rolling in a pair of sweet red-and-gold Chiefs skates, was thrilled beyond measure last June when his athletically inclined 19-year-old son called him up and said he—finally—wanted to learn what’s been his father’s passion for almost 50 years.

“My son said, ‘I want to skate so I can be noticed,’” Egan says. “And I was like, ‘WHAT??!?!’ So that day, I went and bought matching hats, matching shirts, matching pants, everything. And then we came out here and I taught him everything I could.”

The African-American community, Egan says, is full of creative people, each with his or her own way of expressing themselves.

“When you’re on the floor and you close your eyes, you’re really in the middle of outer space,” he says. “You’re going, you’re spinning, you’re turning, you’re in your own world.”

It might be cold and nasty outside the rink. There are idiots and bigots and jerks and racists everywhere else. Plus family issues, bills, mortgages looming.

Inside, though, for a couple of hours on Sundays, the world expands and resembles something like freedom.

“This is our outlet,” Egan says. “This is our escape from everything.”