Sponsored post:

If you love wine, you may have encountered the word “terroir.” Pronounced “tare WAHr,” it is the sum of all things that make one wine taste distinct from the next. These include climate, soil, geography and culture, and so much more. It’s a much-discussed concept, and as with many aspects of wine knowledge it can intimidate. It helps to find an example of a wine from a terroir that really stands out personally, and one that you love to drink. It might be a Napa Valley Cabernet, a Provence Rosé or Bordeaux, if it has a sense of place that you get to sip and savor, you’re on the path to wine enlightenment. You have found terroir.

I first learned about terroir from Jacques Lardière, the long-time winemaker of Maison Louis Jadot. Jacques would talk of “the vibrations” in the soil of Burgundy like a living thing. His wines reflected this—from grand cru to Beaujolais, terroir was the key to everything. Within each vineyard, often row-by-row, he was keenly aware of the distinct personalities at play, in unique soils, exposure, and vintage. He was a steward of the vines, whose job was to develop the character of each wine, and like a great teacher found the best in a student through patience never domination. He had one goal: to create wines that reflected the sites they came from. Terroir was subtlety and his job was to make sure that it came through.

It took me a few years to find my way back. In the meantime, Chianti Classico was finding its way forward, with new regulations and attention to soil, varieties and yields to drive quality. In 2005, I was at an Italian wine tasting in New York and the speaker poured eight wines from DOCG Chianti Classico. The wines tasted of violet and spice served up on a bed of cherry; they were primarily made with the Sangiovese grape (by law a minimum of 80% of the blend, which can also include Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and other approved red varieties); oak was restrained, letting elegance and freshness through. Delicious and mouthwatering, they tasted like a long-forgotten terroir that had improved with age.

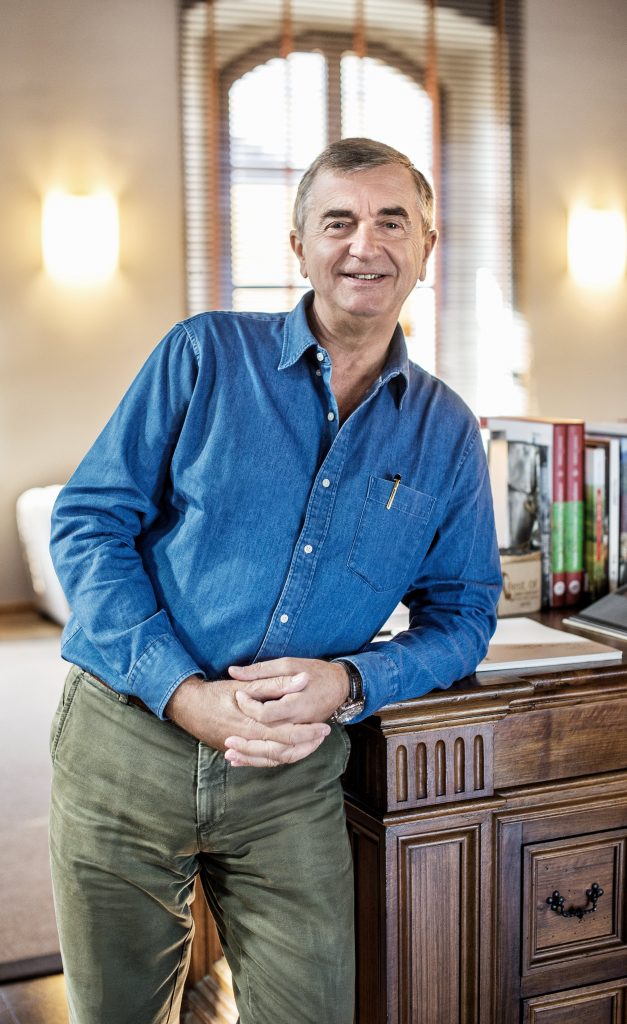

My most recent discovery from Chianti Classico is (ironically) not only the oldest winery in Tuscany, but in Italy: Ricasoli wines have been made at the Brolio estate just northeast of Siena since 1141. That’s over 900 years of continuous winemaking by the same family. This is impressive. But if you ask Baron Francesco Ricasoli for his opinion, what matters most is Brolio. It always comes back to terroir.

The 32nd Baron of Ricasoli, Francesco took over the 3000-acre property in 1993 and has been part of the modern renaissance in his region ever since. 600 acres of Brolio are planted to vineyards on gentle, sloping hills that descend into picturesque valleys, olive trees, oak forests and chestnuts. It’s quite a legacy to oversee and the impressive Brolio Castle overlooks it all; open to visitors, it houses a family tree from 1584, one of the first known images of Chianti Classico. Francesco’s focus is on quality and sustainability; over the years he has mapped the vineyards, identifying the many different soil types and sites that contribute to the personality of Ricasoli wines. They have even discovered their own variation of ancestral Sangiovese, the “Brolio clone.”

Chianti Classico comes in distinct tiers, from entry-level wines (aged up to 12 months) to Riserva (aged 24 months) and Gran Selezione (up to 30), with each delivering age, complexity and more in the terroir department as you move from sourcing grapes from the broader DOCG region to specific vineyards. Like Ricasoli, most producers offer a full range. Try Brolio Chianti Classico DOCG 2015 for a first look at the family’s signature Sangiovese or choose Castello di Brolio Chianti Classico Gran Selezione DOCG 2015 (90% Sangiovese, 5% Cabernet Sauvignon, 5% Petit Verdot), made from the estate’s best grapes. Deep ruby, it shows floral notes, ripe red fruit, licorice and chocolate. It’s Chianti Classico—and terroir—at its best.

Helen Gregory lived in Italy for six years as a child, and has been finding excuses to visit ever since. She divides her time between homes in Sunset Hills and Brooklyn, and works with wine, spirits, beer and travel clients from many different terroir. @gregoryandvine