This spring, COVID-19 precautions changed daily life for everyone in Kansas City. Those in the food and beverage industry were hit especially hard as restaurants and bars limited operations or closed, and many establishments found themselves forced to lay off employees.

Keely Edgington, co-owner of the Westport cocktail bar Julep, opted to shut its doors during the crisis, while Chris Meyers, co-founder of Crane Brewing Co., and Isaac Hodges, president of Messenger Coffee, looked for ways to safely adapt their businesses. Rachel Kennedy, co-developer of North Kansas City’s collaborative outdoor food, beverage, and retail space Iron District and owner of Plantain District, hit the brakes on a grand reopening.

Meanwhile, new initiatives emerged to support KC restaurants and hospitality workers. The Rieger Hotel Grill & Exchange shifted to operate as a community kitchen, explains general manager Kyle Bennett. Open Belly podcast creator Danielle Lehman started Curbside KC, an online directory of what local bars and restaurants are offering during the pandemic, which is designed to help connect businesses with their customers. And after losing his job as the executive chef at Plate, Clark Grant co-founded the KC Hospitality Support Initiative, selling T-shirts to raise grocery money for service industry workers.

Through a series of separate conversations in mid-April, these seven Kansas Citians shared their experiences navigating the industry during this unprecedented pandemic.

Responding to COVID-19

Before businesses open to the public were officially forced to close, owners were already reacting to COVID-19, many during the week of March 9.

Rachel Kennedy: We launched last October and were open for about six weeks. And then we were going to have our grand reopening on Snake Saturday, March 14. That was the week when restrictions started getting tighter and we were starting to learn more about COVID-19. The big parade in North Kansas City was canceled, so we obviously halted our grand opening for the safety of ourselves and for the patrons as well.

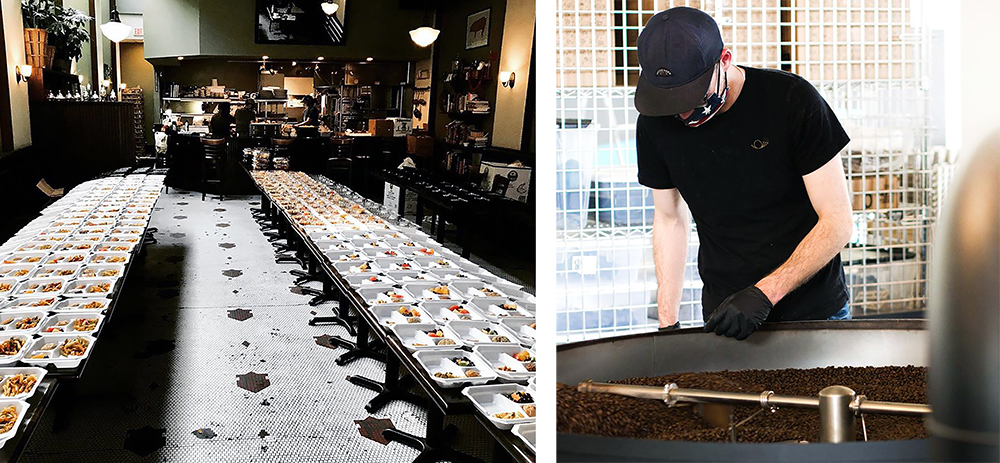

Kyle Bennett: That weekend was when the uptick of concern really started to become noticeable in a restaurant. We saw a huge impact on business throughout that weekend as concerns of the nation were public safety; public health definitely was a big discussion. Fast-forward, that Monday was when we started seeing other restaurants talking about going to curbside to-go, making decisions to essentially stop or transform their normal style of business. As we were trying to stay ahead of everything, we made the decision to stop normal services, but take it a step forward as we recognized the potential for a need to feed our community in a different way than what the Rieger would normally.

On the 16th we sat down as a team. Howard [Hanna, chef-owner] and our director of operations, Becki [Ford], met earlier in the day and they had made the decision to make that call and transform. That night we started feeding people as Crossroads Community Kitchen.

Keely Edgington: Realizing that it was for sure going to happen, not just something we thought was going to happen, was probably about ten days before we shut down. I knew it was on the horizon. I told my employees to save everything you make from here on out. Don’t spend a dime. I was hoping we’d have a little bit more time so they could save up one pay period’s worth of money, but no, not quite.

Christopher Meyers: We pretty much immediately got emails from all our distributors—we had two orders ready to go—saying those orders are canceled and any orders for the foreseeable future are also going to be canceled.

Isaac Hodges: The week of the 16th, we had the layoffs starting to happen for our business. It’s the hardest thing ever when you let go of anyone, let alone over 100 employees have to be let go. That week was horrific and awful, and I really hope we never have to go through anything like that again.

Clark Grant and his wife were both laid off the week of St. Patrick’s Day along with numerous others in the service industry. Inspired to help, Grant started the KC Hospitality Support Initiative, which sells T-shirts to raise money for grocery gift cards raffled off to unemployed and underemployed service industry workers.

Clark Grant: We sold 640 shirts in exactly three weeks. We’ve had about $4,000 in donations. We’re doing pretty well with people helping us out, but the more we can spread the word, the more we can get money out to people. Even after today, I still had over 400 applicants who hadn’t received a gift card yet.

If nothing else, you’re giving people something to look forward to when they wake up in the morning. They go and check their email and see if they’ve won—anything that can take your mind off it. That’s really what our focus is: Helping people eat during this time, making sure people have groceries.

Bennett: That first night, we sent a message out that Crossroads Community Kitchen is going to be operating from 4 to 6; anybody who needs a meal can show up at the restaurant and we’ll prepare it for you to go on a pay-as-you’re-able basis, no questions asked, and we’ll take donations if you want to give them to us, but it’s obviously not a requirement.

On an average day, we’re serving anywhere from 500 to 1,000 people right now.

Adapting to the upheaval

To bring in some revenue, many businesses transitioned to offering carry-out, curbside pick-up or delivery, while others shut down entirely.

Danielle Lehman: As a consumer, I felt like it was pretty confusing to figure out who was offering what, and everything was changing super quickly. Unless you were closely monitoring each restaurant’s social-media feed, it was hard to tell what the latest information was. A lot of my friends who own restaurants were concerned about how to get the word out and I, of course, just wanted to do anything I could to help them. I suggested, “What if I just set up a website where you guys could list what your current hours are, what you’re offering—would that be helpful?” They were kind of like, “Yeah, why not?”

Now we’ve had over 100,000 unique visitors on the site since it launched a few weeks ago, and we have over 1,200 restaurants in the database. I had no idea it was going to become that much of a crucial communication channel for people.

Meyers: We initially planned to completely shut down. We went back realizing that as long as we can still sell beer in the taproom, we’re nowhere near at full production but we can at least try and fill a tank, keep something going to have some new stuff to keep people interested.

Edgington: I knew we had the option to do delivery and cocktails to-go and things like that, but it’s not extremely profitable. It’s all about risk—you’d make a little bit of money, but it’s not going to be enough to make things operational, and you’re putting yourself and whoever that person is at risk because they’re still dealing with the public. It was our feeling that it was more responsible to just shut down all together and wait it out.

Hodges: I think our biggest focus has been to maintain the business, because we knew what our run rate looked like and we knew we needed to maintain revenue coming in, so the online revenue generating has been extremely helpful for us. Our online sales are up 280 percent over the previous 30 days.

Kennedy: With the current situation, our vendors and our patrons aren’t able to experience the benefits of what Iron District truly offers until summer at the earliest, no matter how worthy our concepts are. To help kind of bridge the gap for vendors we launched the Container Club Membership Program. In a nutshell, you’re basically purchasing an invite to attend one of our 2020 private parties and that features a taste of Iron District.

Looking to the future

With the course of COVID-19 still uncertain, businesses have little sense of when they may be able to reopen or what it will look like for them and the rest of the industry.

Bennett: We’re still in the middle of this, and I don’t think we’ve seen the worst of what it’s going to be. Things are changing by the week, and I think they’re going to continue to do so until they don’t, I guess. It’s really hard to put a timeline in place, and that has a huge impact.

Hodges: We can kind of move things around to keep our business afloat. But like in Lawrence, our partner Wake the Dead is completely out of business. She’s selling everything off. It’s hard to see a lot of small businesses that won’t ever recover. I just don’t know how we support businesses like that moving forward in a different kind of way.

Edgington: This isn’t great for any business, but we’re lucky that we had a bit of a safety net built up—most restaurants and bars are not built to sustain this at all. If this happens again later in the year, I don’t know what that looks like. It’s going to be really hard. We have no cash flow. There’s zero cash flow now, essentially. I think once we do open back up, every single penny that we make, we have to be thinking this will happen again in the fall. We have to be prepared for that, just in case. And maybe again next spring. As long as there isn’t a vaccine, this industry isn’t safe.