One night a couple of weeks ago, Chadwick Brooks called an Uber to drive him home to his new place at 55th and Garfield. The driver, a black man, looked back at Brooks, a white man, and said, “Really?”

Really, Brooks said.

“He said, ‘Damn,’” Brooks says. “The driver said, ‘I used to have a weed dealer who lived at 55th and Garfield. That used to be the ’hood.’”

Brooks moved to his new home in the Blue Hills neighborhood east of Troost Avenue about a year ago. He couldn’t pass up the place. A home like it elsewhere in Kansas City was out of his price range, to say the least.

Brooks is a native of Riley, Kan., a town of about 900 people in the northeast part of the state. His new neighborhood, bordered by the Paseo and Prospect, feels like his hometown. “It’s very diverse,” he says. “There’re elderly and kids and all walks of life. It’s a community.”

Brooks, co-owner of Late Night Theatre, is part of a new wave of residents and businesses making their homes and livings in an area of Kansas City whose name sometimes still provokes wide-eyed silent stares from fellow Kansas Citians, even among those who wouldn’t consider themselves particularly prejudiced.

But “Troost” is KC code for many things. Crime. Poverty. Segregation. Inequality. And all the nasty racial thoughts some people might have but keep to themselves. A burgeoning group of Kansas Citians, however, is trying to change the area. Not everyone is happy about it, though.

“It’s bullshit,” said Hakima Tafunzi Payne, executive director of the nonprofit Uzazi Village. “Don’t call it revitalization. It’s gentrification, plain and simple.”

It’s unfair to single out Kansas City folks for drawing borders around themselves. It’s an unfortunate symptom of the human condition.

Nonetheless, the entire metro is Balkanized. There’s Downtown and Midtown. The Downtown Loop. The Crossroads. Westport. Waldo. North Kansas City and Kansas City, North. In JoCo you have the Shawnee Mission East, West, Northwest, North and South school districts—and Shawnee and Mission.

Should an outsider mix one with another they can almost immediately expect to be corrected by the Kansas City Metro Geography Police.

Even in the basement dressing rooms of the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts, stickers on mirrors remind visiting artists and musicians they’re in Kansas City, Missouri,” lest they step to the mic and mistakenly tell their adoring fans, “It’s so good to be in Kansas.”

Troost Avenue is the same but different.

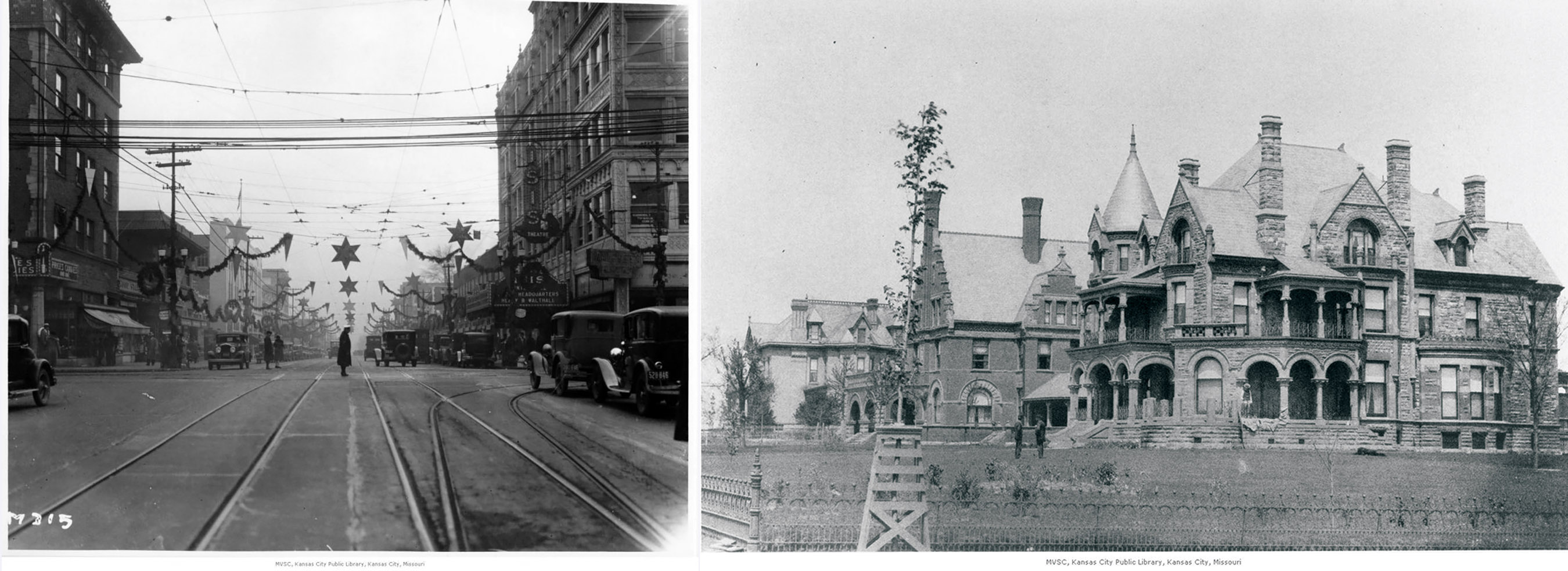

Once no more than a path Osage Indians used to truck their canoes to the river, the road that became Troost has been many things over the years, according to a report for the Kansas City Catalytic Urban Redevelopment, prepared by the BNIM architecture firm.

The street is named for Kansas City’s first resident physician, Dr. Benoist Troost, and his wife, Mary Ann. The Troosts were slave-owners, as was the Rev. James Porter, whose plantation was near today’s 31st and Troost.

Between 1865 and 1912, the area had so many fancy mansions and wealthy residents, it was nicknamed “Millionaire’s Row.” By the 1920s through the ’50s, the mansions were gone, and it was a thriving commercial district. Almost a second downtown, with theaters, dime stores, banks, and car dealerships lining the avenue.

Racially biased-lending practices segregated neighborhoods not just in KC but across the country before and after World War II, as banks and realtors directed whites to one area and blacks to others.

In 1954, when Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was supposed to result in school desegregation, the local school district border was drawn at Troost, effectively segregating white students from black. So, while some borders are merely lines on a map or imaginary demarcations, the “Troost Wall” is something all too real. The road is like some strange borderland, an urban Venn diagram where everything Kansas City intersects, sometimes painfully.

Park at the Dollar Tree on Troost and head west two blocks to find fenced-off homes with fine-art sculptures in manicured yards. Walk two blocks in the opposite direction and see occupied apartment buildings that look as though they’re cleaved in two and about to fall in on themselves.

Rockhurst University and the University of Kansas City lie to the south. To the north is the City Union Mission, where dozens upon dozens of homeless men spend each night sleeping in gymnasium-sized rooms filled with bunk beds only a little more than shoulder-width apart.

In the last decade, though, millions of dollars have been poured into development projects in the Troost corridor, bringing about the kind of change that some tend to dread.

It’s no small irony that you can stand at about 18th and Troost and see a big red sign on a tall building that reads “TENSION” (as in Tension Envelopes).

Regardless, people like Chris Goode are doing what they can to bring the various parts together and ease any tensions. Goode is the founder of Ruby Jean’s Juicery, which just celebrated its one-year anniversary at its 30th and Troost location.

“I would consider us early adopters,” he says of Ruby Jean’s move to Troost. “I grew up not far from the area. For me seeing this corridor transform, it’s a great thing. There’s a lot of opportunity for us to create a conversation around equality, diversity, and inclusivity.”

He’s not immune to the criticism and the concerns of gentrification. He hears it. He empathizes. “There is a concern how it’s being done and how it’s affecting people who have been there for decades,” he says. “Being a kid who went to daycare across the street, I see it as opportunity as opposed to anything negative.”

Goode says his customer base is nearly 50-50 black and white, with sprinklings of other ethnicities. People aren’t just gathering for his business; they’re gathering for health, for community. “We were able to eradicate a food desert,” he said. “But you also have minority-owned entrepreneurs, you have big money commercial development. It’s just a snowball that’s being formed really quickly.”

The Ruby Jean’s location at 30th and Troost has been something of the epicenter of the revitalization. The recent Troostapalooza festival was held in the area. Goode is excited not only to see how far this blighted and neglected part of the city has come, but also to dream about where it could go. “I hope it looks like New York in five years,” he says. “You see affluent, you see middle class, and you see all kinds of people putting aside differences and creating community in an area that’s been flipped on its head from racism to collectivism.”

Some worry that as the area becomes more developed, the more likely it is that one of Kansas City’s unique African-American communities will be rubbed out, much like the indigenous peoples were removed when white settlers came along all those years ago.

“I’ve lived here 56 years, and I’d know revitalization if I saw it, and this isn’t revitalization,” said Hakima Tafunzi Payne. “I’m seeing the absolute destruction of my community.”

Payne is the director of Uzazi Village, a nonprofit helping mothers—particularly African-American and Hispanic mothers—with infant and perinatal care.

In just the last six years, she’s seen property values price people into moving away. She’s watched tax breaks go to out-of-state companies. And she’s witnessed a marked change in demographics—from low-income black people to affluent white people. “The development isn’t to help us,” she says. “It’s to drive us out as quickly as possible.”

Payne said she would rather see the city invest in some basic improvements that would improve the quality of life for current residents. Instead, she sees outside developers creating million-dollar developments unaffordable to area residents.

Most frustrating is she feels like her community members don’t have a voice, or at least they’re not being heard. “They don’t know anything about me or my community, nor do they want to know,” she said. “They’re not interested in our value as people. They’re just interested in the value of their property.”

Crissy Dastrup, co-founder of the Troost Market Collective, has a different vision, intended to bring people together. She helped get 14 murals painted down the west side of the 3100 block of Troost. She helped organize the first Troostapalooza, a large-scale festival in the area. Next spring, the collective is considering a farmers/makers market.

Dastrup lives off of Campbell and Armour and goes to church near 25th and Brooklyn. Before she became involved with the collective, she’d drive down Troost and think how cool it would be if someone put some time, money and resources into the area.

She’s heard the criticism, too. In her experience, though, people on the east side of Troost have a broad range of opinions on what can and should be done. There’s no one voice. There’s a lot of difference of opinion among all residents.

“The east-side leadership has for a very long time wanted development,” she says. “They are the ones who held Mayor Sly James to his promise to put resources into the east side. We’re just finally beginning to see some movement there.” Dastrup says she understands when people worry they’ll lose homes that have been passed down through generations. They’re stuck between low property values with no area improvements or being priced out because improvements need financing. “Our city council people can do property tax freezes on homes in that area; that’s something that is done all over the country,” she says.

Dastrup’s hope is that the city will find ways to preserve Troost as an historic jewel while simultaneously spurring development and updating buildings neglected for years. “It’s not that you can’t have both,” she says. “We just have to hold our city leaders accountable.”

Dastrup also gets it when people worry about gentrification. “Is gentrification a thing? Yeah. Can it be horrible? Uh-huh,” she says. “Do we have the ability to protect people and to help them to stay in their homes? Yes, we have that, too. Can we do that while building nice things? Yes, we can.”

The hope of change was evident at Troostapalooza, Dastrup said. People came from the east and west side of Troost, as well as from all over the city. Seeing and talking with so many people who feel the same desire to see Troost thrive staggered her, in a good way.

“I think everybody wants to be part of erasing that dividing line,” she says. “I think that affects us all on a subconscious level. We know that’s not who we are and that’s not who we want to be. But it’s really hard for people to know how to fix it.”

Ruben Alonso, president of AltCap, a community development financial institution whose mission is to fund Kansas City’s under-served areas, says the company will move its headquarters to Troost next year. “When we were looking for more space, we wanted to be in an area where we are trying to help stimulate economic activity and investment,” he says. “Troost was perfect for us to stay true to our mission and make a statement.”

Alonso compares Troost today to the Crossroads in the 1990s. Now that the Crossroads is developed, people are looking elsewhere for opportunities. This, of course, lends some credence to both sides of the Troost revitalization/gentrification argument. Some are being priced out of the Crossroads; others are finding great opportunity there.

“The Crossroads is a really hot submarket in real estate in Kansas City,” he says. “It has a cultural identity with the arts. But it seems like there are more banks down there than art galleries at this point. That just shows how popular it’s become, and I think you have a lot of the similar potential elements in the Troost corridor.”

Chadwick Brooks was living near 43rd Street and McGee when a friend said he needed to come see a house at 55th and Garfield. He wasn’t even looking to buy at the time, but he was sick of the noise at McGee.

The house on Garfield was perfect. A solid brick home. Built in 1917. All new appliances. Completely redone. Everything was just as he would have designed it.

And most of all, it was affordable.

“I’m single and buying it on my own and there’s no way I could have afforded this house if it was in Brookside,” he says. “It is a full-on Brookside house in Blue Hills.” He says he loves his neighbors. He almost immediately felt a sense of community.

“My street reminds me of the small town I grew up in,” he says.

Brooks says he’d heard the stories and the prejudices about the neighborhood. He even looked at crime stats and found zero difference between where he was living and where the new house was. After he looked up that information, he wondered why he did it. “We have it ingrained as Kansas Citians about the ‘Troost Line’,” he says. “I’ve lived on the Westside. I’ve lived downtown in lofts. I’ve lived in midtown. All over the place. This house is in a neighborhood. It is quiet. It’s this close to Whole Foods. It’s this close to 71. It has everything.”

The majority of his friends aren’t familiar with his neighborhood, but they know 55th and they know Rockhurst. And they know Troost. “I’ve had just a couple of friends that I kind of wanted to bop in the head for saying ‘Ew’,” he says. “But I let them have it. Nuh-uh. Don’t discriminate, period. And you have to say it out loud, even if they’re your friends. The majority, though, haven’t said anything.”

Novelist Whitney Terrell grew up in the area and is an associate professor at UMKC. Two of his novels, The Huntsman and The King of Kings County, focused on the historically fractured race relations in KC.

He says he didn’t feel entirely comfortable being a voice for everyone in the area. That voice should come from those African-American homeowners. “I would just hope the gentrification process isn’t funneling money out of the community,” he says.

He does own property there. He’s seen all the new houses going up. Not everyone who lives in the area is African-American, though that’s the primary demographic.

But race isn’t the only issue around redeveloping, reinvigorating and reinventing Troost. “It’s going to be a complicated conversation,” Terrell says. “Generationally, people in those areas have lost a traditional American way of building generational wealth, which is to have the opportunity to have your property escalate in value.”

His parents, for example, bought a house at 64th and Locust in the 1960s and their house has gone up in value nearly tenfold. In general, that escalation has not happened on houses just a few blocks to the east.

As for the “Troost Wall”? Terrell says for many people who live in the area, that divider is already functionally erased. “Students and people of all ethnic backgrounds live in that area and do not see it as a problem,” he says. “It’s been historically an issue and something that’s talked about. But once people start asking ‘Has it changed?’ that usually means it’s already changed.”