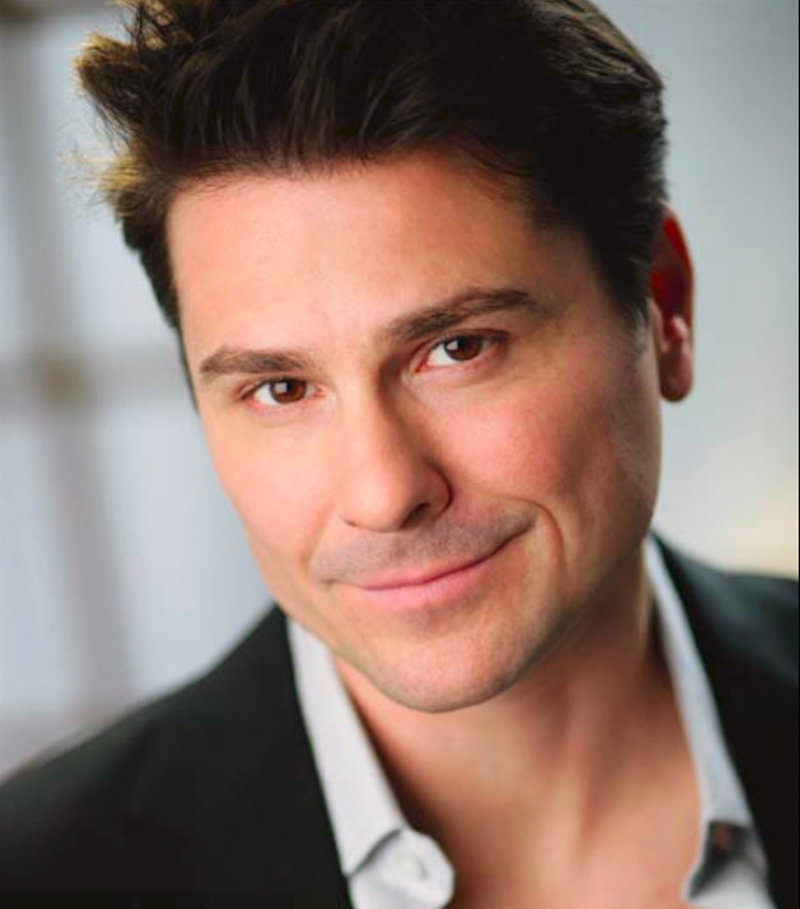

A quiet kid from Shawnee Mission West who remembers being “in his own world” because he didn’t wear needed glasses out of vanity went on to find success on both sides of a movie camera lens. Actor and filmmaker Brian Vincent was born Brian Vincent Kelly in Kansas City, lived in Raytown until age 10, then moved to Overland Park.

Vincent’s 2023 documentary, Make Me Famous, about the rebellious art scene in 1980s New York, is currently the third-highest grossing art documentary of 2023 in limited release, currently in its 16th month exclusive to theaters.

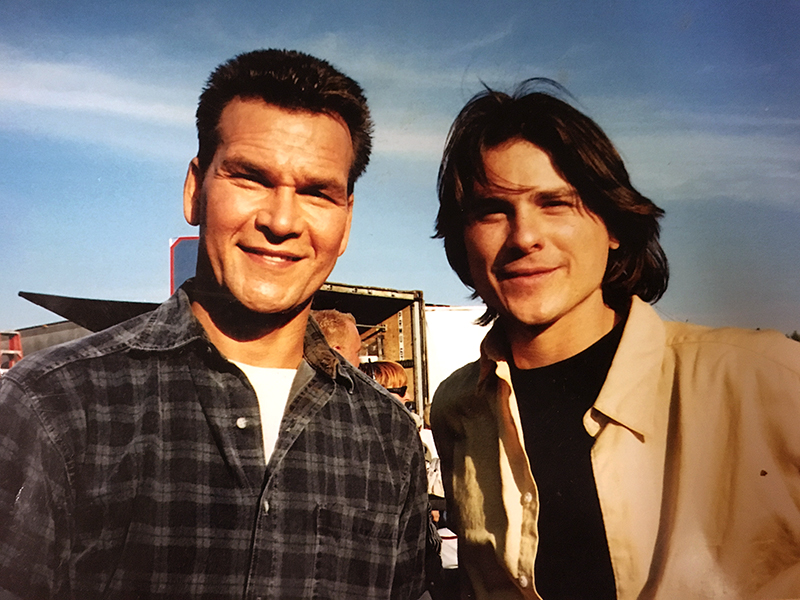

Vincent graduated from Juilliard in 1994, starred in Animal Room (1995) with Amanda Peet and Neil Patrick Harris and appeared in The Deli (1997) with Gretchen Mol, Blue Moon (2000) with Ben Gazzara and Rita Moreno, and Black Dog (1998) with Patrick Swayze.

Vincent lives in New York with his actress wife, Heather Spore, who performed in Wicked on Broadway for ten years. He spoke recently with IN Kansas City from the couple’s apartment in East Harlem about his formative years in Kansas City, the lucky breaks that changed the trajectory of Make Me Famous, and his next film project.

Shawnee Mission West has several famous acting alums, including Paul Rudd and Jason Sudeikis. Did you know them?

Paul was a year older than me, but he was class president, and I was just a guy going to school there. [Laughs] His talent baffled me. I remember when he was in high school, and he came to my junior high and did improvisation. That was pretty unforgettable. Then I did forensics with the famous Sally Shipley, who also taught Jason, and Paul was in that class. But when I was in class with Paul, I was so shy I could barely talk. The very next year after he had left was when I decided I wanted to be an actor, and I was like a different person then.

All your bios say Juilliard, but I read that you also attended Emporia State University in Kansas. What was that like?

I loved Emporia State University. Seth McClintock taught me drama. He was a legendary theater director at Shawnee Mission West. He really believed in me as an actor, even though I only picked it up in my senior year. He cast me in every play. He advised me not to go to [University of Kansas] because he thought I would get lost in the shuffle there. He recommended Emporia because they had a brilliant theater program. I went there for two years, and there were talented people who worked with me. I’m almost 100 percent sure I would not have gotten into Juilliard if I had not gone to Emporia first.

Have you stayed in New York ever since you were at Juilliard?

Yes. I love theater, and New York has always been very good to me. I did live in Los Angeles twice for pilot seasons, but I just didn’t take to it.

Why not?

It’s a different lifestyle. It’s not theater driven. I just always had more luck and more love for the city of New York. I thrive better here.

How did Kansas City shape you as an artist?

In Kansas City, I always found so much support, and they love theater there. People really came out to see the shows and rooted me on. When I did forensics, I think I won state—I won something—and I got to go to nationals for drama. That made me think about this impossible dream—maybe I could do this.

Do you still have connections to Kansas City?

Oh, yeah. My father still lives there with his wife and my mother lives in Independence, Missouri, and I have a huge family on both sides, and they are rooting every second for anything Heather and I do.

Do you have any sports allegiances?

Oh, yes. I never stopped being a Royals fan. And I never will.

My dad didn’t want me playing football when I was a kid, so I wasn’t much of a Chiefs fan.

That’s a brave thing to say.

[Laughs] I support them!

Was your original idea for Make Me Famous to tell the story of the 1980s arts scene in the East Village or to examine the life of this painter, Edward Brezinski?

I fell in love with the 1980s arts scene when I first came to New York and read Cynthia Carr’s book, Fire in the Belly. It blew my mind.

When did you read it?

It might have been 2015. I had heard about the art scene before, but by the time I came to New York it was 1990 and the art scene was long dead by then. The book made me think, “Wow, what a different and exciting New York this sounds like, and all these different people came out of that scene—Madonna and Eric Bogosian and Basquiat and Keith Haring. And I was like, why? Why did New York produce so many artists in that moment and not as many now?

Reading that book and others reminded me of going to Juilliard, because you could do a project and just shout out, “Who wants to do this with me?” And you’d have an actor and a musician and everybody all performing together.

That’s how the arts scene was in the ’80s because they’d all come to New York, and New York was totally broke. It was coming off Gerald Ford’s “drop dead” to New York. [In 1975, when Ford denied the bankrupt city a federal bailout, the Daily News ran the headline “Ford to City: Drop Dead.”]

There was no way artists could get famous the conventional way, but rent was so cheap they could all live out their Bohemian fantasies. They rented storefronts or performance places in the Lower East Side and performed for each other. As Eric Bogosian said, the most creative people, the ones that surprised you the most, rose to the top. And all of a sudden, people started getting famous.

So, you’re interested in the scene, but when do you trip across Edward Brezinski?

So Heather’s on Broadway but I’m in between work as an actor, so I’m working as a waiter in catering. And I tell a fellow waiter—his name is Lenny Kisko—“I’m really into the 1980s art scene.” And he says, “I collected this one artist all through the ’80s. You should come see this work.”

I go to his apartment and every surface is covered with Edward Brezinski paintings. He said, “I spent all the money I made paying for all this art thinking maybe he’d get famous, but then he disappeared, and no one knows what happened to him.”

What did you think of the paintings themselves that day, apart from Brezinski’s story?

The artwork spoke to me. It’s expressive, it’s beautiful. I thought it was really good.

The film draws raw energy from amazing contemporaneous videos. Did you know they existed when you started?

No! It was pure dumb luck. We stumbled on an incredible video on YouTube with Edward Brezinski in it, and the poet Miguel Piñero was performing. And Lenny Kisko said, “Hey, that’s Ed Brezinski’s apartment.”

So I reached out to the person who made that video, and he said, “I have 100 hours of this stuff.” And what’s so fabulous about that is, you can’t find that in 1980, 1981, 1982. And had we not picked Edward Brezinski, that footage may never have seen the light of day.

You’re not of the art world, but you immersed yourself in it for several years working on this project. Do you think if Brezinski had had more business savvy or if the right gallerist had taken him under their wing, he could have been famous, or do you think the work he was doing was not original enough to be in the top tier of that scene?

I think he could have broken through and been considered one of the finer artists of his time. There’s almost no doubt about that, because he’s talked about by almost all of the main players from that time. The way Lenny Kisko talked about him that first day was so animated and exciting. And then I started hearing these other stories about him.

Annina Nosei, who discovered Basquiat, was his first gallerist. She has an amazing story about Edward in the movie. It has to do with his inability to cooperate.

What were the most emotional moments for you conducting the interviews about this person you never met but who left such a large imprint on others?

It was easy to forget he was a real person. I’m an actor so I almost always think of people as characters anyway. But interviewing people when they would tear up and it was clear they missed him a lot and wondered what happened to him was emotional. And you have to remember, AIDS devastated this community. So many disappeared in 1990 and beyond that people almost didn’t want to find out what happened to him because the answer is almost always the same.

At the same time, the project brought a lot of joy to people because they are so used to people asking the same questions about Basquiat and Haring. So they were delighted by the angle.

Full disclosure: I liked the film a lot more than I thought I would. And my husband, who has very little interest in contemporary art, said, “I don’t care about the subject, but this is holding my attention.”

Yay!

It’s more interesting, more universal in a way to look at someone who is very talented, tried very hard and didn’t make it big. But the film is also technically excellent. Where did you learn how to write, direct, and edit?

In 2000 I decided I wanted to be a filmmaker. I had a friend who owned a quasi-television studio, and he hired me to make boring corporate videos. So I learned lighting and how to work with a crew while being in a place I wouldn’t fail.

Why do you think this movie hasn’t gotten a distribution deal yet?

When we finished the movie, we were offered distribution, but no one wanted to release it in theaters.

Why was that important to you?

Firstly, I thought it could potentially be a hit in New York but secondly, I had always made the movie thinking that it’s the kind of movie that should be seen with a crowd.

Why?

Heather and I are theater people, and it’s designed almost like a theater piece. So we thought, let’s just try it. Heather has a knack for calling theaters and getting them interested.

But it wasn’t New York that embraced it first. It was Toronto. We were offered ten screenings at the beautiful Hot Docs cinema in Toronto. We got that booking because Sundance was going on at the same time and nobody wanted to show their movie then. We got onto the cover of the Toronto Star arts section, and then Edward’s family, who are from Canada—they didn’t know about the movie—called Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and said, “Our long-lost cousin is in this movie,” and CBC did a show about them seeing the movie for the first time.

Because of that, we were offered to come to London, and we were a surprise hit there. It ran for three weeks.

Then the Museum of the City of New York offered us a screening. It sold out in 48 hours. That’s when three other theaters offered to run it, and it turned into a hit. We made $11,000 in box office in one week, which would be impossible with streaming. What streamers do is they say, “Thank you very much, we’ll send you a check, and I hear filmmakers all the time say, ‘Look, I got a 15-cent check’.”

So it would be foolhardy of us to stop this run in theaters.

What’s your next project?

We’ve actually been working on a new project for a year. Going around the country and abroad, I got a sense of who is coming to these theaters and the kinds of things that might appeal to them. When I was a kid, I was always interested in James Dean. I’d seen all his movies, and he got me interested in acting. And I thought, I don’t think there’s ever been a movie about James Dean in New York in the ’50s and what was it like for him here and how did he make it?

We interviewed his best friend. He was 95. He just recently passed away. His name was Lew Bracker, and he just blew us away. He told us all these interesting things about James Dean. So we’re trying to capture, again, an era that is long gone. And I’m trying to reintroduce Dean to young people—what was exciting about him but also what was exciting about New York in the ’50s.

Interview condensed and minimally edited for clarity.