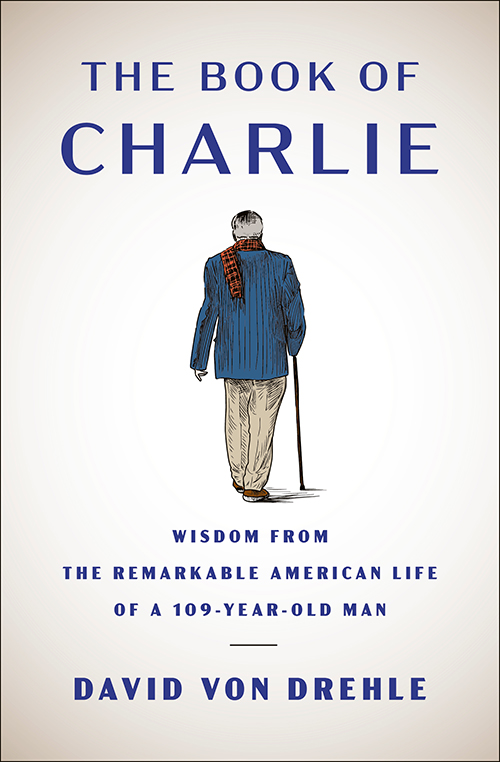

Serendipity is when a gifted writer moves to a new town and discovers his charming, energetic neighbor is a celebrated physician, bon vivant, and—oh, by the way—more than a century old. Dr. Charlie White’s life, which began before cars and ended with humans orbiting Earth on the International Space Station, was a tale waiting to be told, and Washington Post columnist and Mission Hills resident David Von Drehle was the person to tell it. The Book of Charlie: Wisdom from the Remarkable American Life of a 109-Year-Old Man (Simon & Schuster) comes out in May.

Von Drehle grew up in Aurora, Colorado. After earning a Bachelor’s in English and philosophy at University of Denver and a Master’s in English literature at University of Oxford, he discovered he wasn’t cut out to be a professor, the life he’d imagined. He returned to what he knew: journalism. While still in high school, Von Drehle had talked himself into a position on the sports desk at the Denver Post, a job he kept through college, while also editing his college paper. After college, he was hired by the Miami Herald, eventually becoming their New York correspondent. When the Herald closed the bureau, Von Drehle, reluctant to return to Miami, landed his dream job in 1991 as the Washington Post’s New York City bureau chief.

In 1993, Von Drehle moved to DC, where he met and married White House correspondent Karen Ball. In 2007, Time offered Von Drehle a job he could do from anywhere, so the couple and their four children moved to Kansas City, Karen’s hometown.

Von Drehle has authored several books including the bestseller Triangle: The Fire that Changed America (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2003). He spoke by telephone with IN Kansas City from his home about his remarkable friendship with Charlie White and what it taught him about the art of living.

The Book of Charlie opens with a wonderful scene of you sitting on the floor of a dark hallway reading chapter books to your children by flashlight. Why did you forgo a couch and ambient lighting?

I wanted to get them all in their dang beds. If you read on the couch, when you finish reading, you’ve still got the transfer to the beds—times four. But when I would get them all in their beds and read from the hallway, they would drift off, or at least be captive. So, it was strategic in that way.

That must have created really cool memories for your kids.

I hope so. It was great memories for me. I really enjoyed that time. We started the tradition in our house in Washington, DC, where the four kids were in three bedrooms and all three rooms converged at the top of the stairs. The rooms here were a little farther apart, so I had to read a little louder. I loved it. I miss it. I wish I could do it every night.

You knew Dr. Charlie White from the time he was 102 until he died at 109. One of the first times you saw him, he was in his driveway bare-chested in swim trunks, washing the sports car of a lady friend who had spent the night. What was your inner reaction to that scene at the time?

That this 102-year-old guy seemed to be finding more time for his romantic life than I was. [Laughs] And what’s wrong with this picture, you know? At that point, the kids were between 4 and 9. It wasn’t exactly the Playboy Mansion around our house.

But more seriously, I was just blown away by this life force.

Did it instantly shake up your conception of what life after 80 or 90 looks like?

It absolutely did. I immediately recognized, as soon as I met Charlie, that he had won the genetic Powerball. There was a lot of luck going on there in terms of his health. So, I wasn’t necessarily looking at him saying, “Hey, that’s going to be me.”

We like to tell ourselves we have control over what’s going to happen to us, but we don’t. It wasn’t like, “If I take the right vitamin or do the right fitness thing that can be me,” so much as it was just, “Wow, you should keep going as long as you can keep going.”

Because I do think some people put speed limits on their lives. Like, “OK, I’m X years old now, I better be slowing down.” Charlie clearly was going to run all the way through the tank.

That’s what I enjoyed so much about the book, is that you’re clearly not in search of the answer to “How can I live longer?” but “How can I live better?”

Yes, no matter how long the life is.

In Charlie’s 109 years, there was enough adventure and drama for a Hollywood film—loss, wars, happy and unhappy marriages. Charlie’s life could really have gone either way. His circumstances could have provided an explanation for two very different types of people.

Yes. Yes.

When Charlie is retelling his life, he’s always focusing on the happy parts. Everything was a lark, a great time. So that makes me wonder: What do you think is more important—what actually happens in our lives, or the way that we remember it?

The way we remember it—if those are my two choices. I think there’s a third alternative that I would put in there, which is how we choose to experience it in the moment.

What do you mean?

Every event that happens to us, we live with it a lot longer in memory than in the experience. In the book I talk about Charlie narrating his own life and making the choice to make it a happy story. Even though in another place I quote him saying, “I don’t really ever remember being happy. We didn’t think about stuff like that.”

So, it’s not being a Pollyanna. It’s not pretending that hard things were easy or sad things weren’t sad. It’s more of a recognition that there are hard things and sad things in every life and that’s part of the whole adventure.

You said that Charlie opened up to you more about his first wife’s struggles with depression when he learned that you had also experienced similar circumstances with loved ones. What did you learn from Charlie that you didn’t know before about dealing with anguishing problems that are outside your control?

I learned that it’s all about the going through it. Charlie really taught me a lot about being in the present. The past is gone, the future is out of our control, and what we have is the moment happening right now. To live in it and embrace it with positivity and optimism even if it’s something bad.

We all have confirmation bias; we’re drawn to stories that reinforce our world view. As you were sifting through Charlie’s life in writing the book, which aspects of his nature did you already share and so were easier to understand?

I think Charlie and I, part of the reason we hit it off, was the fact that we’re a lot alike in that we both recognize that we’ve got this one shot on planet Earth. It’s a pretty unlikely thing that any of us are here, no matter how cosmic a view you want to take. We’ve looked all around everywhere we can see as a species and there’s no other place where we could live. There’s no other place with air to breathe and gravity to hold us down. It’s kind of weird that a planet even exists. It’s weird that human beings can love and enjoy beauty.

Being sad about it and gloomy and depressed about it, being angry about it, doesn’t make it any more fun or any easier to bear. And it’s going to come to an end as well. That suggests, as we grow and mature, a kind of stance about the world—I’m going to do my best to make as much of my trip, however long or short it is, as I can. That’s all I can do.

You lay out a theory in your book that we spend half of our lives as complexifiers and the second half as simplifiers. Can you explain that concept?

It occurred to me as I was trying to distill what is the take-away lesson from Charlie that we start out as innocent little kids, trying to figure out the world. And the first thing we figure out is, “Wait a minute, there’s a lot more going on here than I thought. Things aren’t as simple as they look. Mom and Dad are not perfect. I’m not safe and sound all the time. Some people are trying to trick me.” It’s realizing the complexity of the world.

But then later—certainly true of me, true of Charlie—you start to drill down past that and realize that there are some simple truths about how to live, and how to be happy, and how to be useful to the community, and to connect with other people and to get meaning out of life.

It all boils down to: Be kind to people. Take joy in life. See the beauty in the world. Look for the best in other people.

Yes, the world is complex. Yes, life is going to throw you curveballs. But what you do about that, how you react, how you live through that complexity is really quite simple.

Do you have retirement plans, and what did you learn from Charlie about how to have a successful retirement?

Let’s say that I have retirement hopes.[Laughs] I love the idea of it, but how I’m going to extricate myself, uh, I don’t know. But what I am going to follow Charlie on for sure is to be engaged all the way up to the end. Charlie loved medicine. [After retirement] he kept going on grand rounds, he went to meetings, read the journals. He kept up with that passion until he basically went into the nursing home at 108. That’s something I definitely want to model. I don’t necessarily want to keep punching the cards that I’ve been punching. For 45 years, I’ve basically been typing for money. I may not want to be on a deadline typing another thing …

But there’s something about storytelling.

There is. And I like it. I hope this isn’t my last book. What I absolutely am not going to do is sit in my house, not meeting people, not having conversations, not engaging with books, while one by one my little crowd of friends disappear.

My mom was influential on this with me, as well. She never stopped making friends. I think that’s so crucial to having a happy old age. Charlie made friends with me when he was 102. A lot of 102-year-olds are not looking for new friends.

Are there things you would like to do if you had more free time?

Sleep. I don’t mean to sound like a smart ass. Before I was married and in management, there were weekend days when I would have a book that I was into, and I’d stretch out on a sofa, and I’d go between reading and napping for 14 hours. I’d like to do that again before I die.

Interview condensed and minimally edited for clarity.