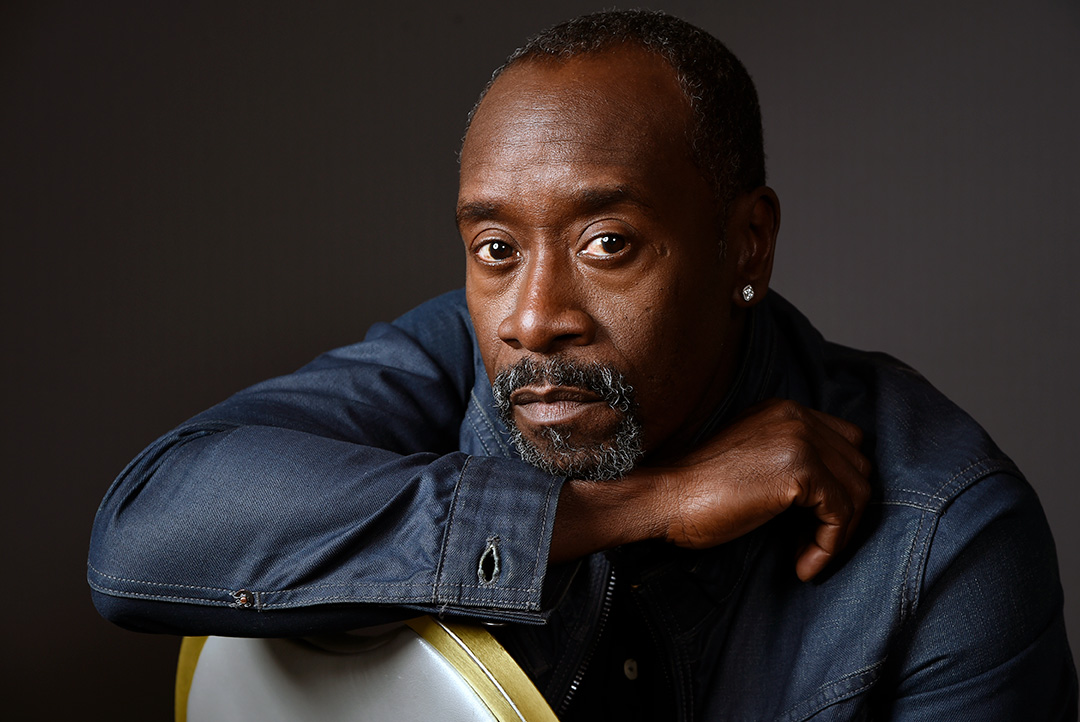

Fatigue hangs off the edges of the smooth, familiar voice, dragging it a semitone lower and half a beat slower. Kansas City’s most critically acclaimed living actor, Don Cheadle, has just finished filming a new Showtime series, Black Monday (premieres Jan. 20), and the accelerated shooting schedule has left him beat down and sick again. He has yet to film a show where he doesn’t get sick by the end, he confides.

Phoning from Los Angeles, home base for Cheadle, his wife Bridgid Coulter, and their two daughters, Amana, 23, and Imani, 21, he answers questions with deliberate precision about the new show and past heavy hitting roles (if you haven’t treated yourself to a retrospective of his amazing character work, start with the films Devil in a Blue Dress, Boogie Nights, Traffic, Crash, Hotel Rwanda, and Traitor, and then binge watch his Golden Globe-winning performance in the Showtime series House of Lies).

But when the conversation turns to his humanitarian work in Sudan and environmental activism fighting climate change, he shifts into a higher, easier gear. This is clearly where his passion lies, the thing—despite his enormous gifts for acting—that matters.

In 2007, Cheadle co-authored with John Prendergast Not on Our Watch: The Mission to End Genocide in Darfur and Beyond. The book goes beyond reportage and lays out, in the best tradition of Martin Luther King’s “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” a call to specific action: Raise awareness, raise funds, write a letter, call for divestment, start an organization, lobby the government. (To learn more or get involved, go to enoughproject.org.) And his climate-change work includes slipping into the role of documentary journalist in absorbing videos that can be seen at theyearsproject.com/correspondent/don-cheadle.

You were born in Kansas City, but moved around a lot as a kid. Does Kansas City still feel like home?

Yes. I have a lot of family that still lives there. It’s a very grounding element, having the family there. It’s a touchstone, it keeps you from getting too far away from who you were. I come back as often as I can because it’s very important to me, and I always have a good time with my family.

Black Monday takes the audience back to Oct. 19, 1987, the day of the worst stock market crash in Wall Street history and offers up a fantastical alternative version of how it happened. You play a character named Rod “The Jammer” Jaminski. What kind of a dude is he? Is he like you at all?

I think he’s very different from me. He’s a complete banana bird, an insane kind of a gambler, somebody who would rather push all his chips in the middle waiting for that last card to come, not having a hand yet, versus knowing that he has a hammerlock. He takes way more chances than I would ever take in my life.

What excited you about the series and made you want to sign onto it?

I think it’s very funny. And the humor is deployed like a machine gun. We’re trying to walk a line, and sometimes you only find the line once you’ve crossed over it—you get back on the other side and go, “Oh, that was over it.” So that was very interesting and exciting to me, to see how far we could push things.

I also liked showing what that time was like, in terms of the excesses of what the traders were doing, the unchecked greed.

“Black Monday can be seen as a cautionary tale, but hopefully people just laugh. We want to smuggle in the seriousness, and the best way to do that is with humor.”

We are still living with the fallout from that debacle.

Absolutely, and some people think we’re headed back in that direction today, with all the deregulation and the loopholes not ever really being closed after the housing crash and the credit crash. A lot of the same players are still in place. Black Monday can be seen as a cautionary tale, but hopefully people just laugh. We want to smuggle in the seriousness, and the best way to do that is with humor.

You and George Clooney issued a report two years ago about war profiteering in South Sudan. Can you give us an update on that situation?

We are focusing now on the oligarchs in Sudan, these power mongers that are robbing the country of all its resources. They are stealing from the coffers, including international financial aid. So we are attempting to go after the banks that do business with these individuals. Instead of going directly to [the banks], we are going to the people who are working with them and saying, “This is what you are supporting. This is what you are involved with. We want you to back out.” We are actually getting a lot of traction. Because the oligarchs’ biggest fear is that they won’t be able to be players on the international market. They won’t be able to operate with the largesse they are accustomed to.

What are the stumbling blocks?

The UN member nations that have been tasked with addressing this are not pursuing it as strongly and substantively as they need to be. So we are always pushing this rock uphill.

What is the thing that gives you hope?

Under this administration we have been able to get more done because nobody is paying attention (laughs).

It’s a disheartening time for activists like you who care about climate change. Do you feel like you are having any success on that front?

Well, I just watched a video of representatives of this administration proclaiming at the UN climate conference [in Poland] today that new technologies in fossil fuel are going to be what get us (starts laughing) to a better place (more laughing). I mean, they were laughed out of the room and people were chanting “Shame on you.” The only people who share this view with us are Saudi Arabia, China and Kuwait—that’s our team. It’s really not a good look for us right now.

But I’m hopeful that with the results of the election and what’s happening in the House [of Representatives] on this issue, there’s going to be a lot of work done. I think Nancy Pelosi is moving this forward now on climate, based on the work of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who has been the one to really lead the way.

“When I have an opportunity to speak with people who put a camera in front of my face, a mic in front of my face, I’m going to speak about the things I think are important, the things that matter.”

Why do you make the time, when you don’t have any to spare, to be so involved in these causes outside your profession?

Well (long pause), I feel it’s an internal mandate of sorts. If all the fame and the celebrity is just so you can buy more stuff it feels very hollow and empty. That was never part of my makeup, it’s not what my family is about, it’s not what my values are. When I have an opportunity to speak with people who put a camera in front of my face, a mic in front of my face, I’m going to speak about the things I think are important, the things that matter. And not just talk about it. Be about it.

You are active on Twitter under your own name, @DonCheadle. That is a scary place to be outspoken about politics these days. You draw the usual nasty insults and outrageous attacks without responding in kind. How do you maintain that composure?

(Laughs.) Because outrageous things are ridiculous. If you’re saying something insane, I feel bad for you, because you are insane. The things that upset you are usually things that have some traction, and then you’ve got to check yourself, like, “Oh, that upset me, so they may be speaking some truth, and I’ve got to investigate myself now.” Also, I guess I feel insulated, because I don’t think anything that happens on that platform is going to really affect me… My wife has been worried about it because people are crazy, and crazy travels, and it’s not hard to get to me. I don’t walk around with body guards and a team. If someone wanted to get to me, they could anyway.

So you don’t feel like it is an acceptable choice to remain silent in these troubled times.

Absolutely not. We have to lean in and take our shots and get knocked around. A lot of times what happens in that space (Twitter) with people that start out in a very combative posture is that we will keep talking and we will come to some agreement about something. Sometimes I go in on the person to be funny, but usually I try to talk about the thing: I’m not attacking you, I’m attacking the thing.

I don’t think anyone anticipated how much actual power (social media) had in both directions. When you think about how Mark Zuckerberg created Facebook as a platform for rating women, it’s not hard to see why he didn’t put certain things in check, and now you can directly point to how it has had an influence on our elections. It’s pretty nefarious in many ways. So it can be a scary place, but you can’t not participate and let the crazies control the narrative.

What are you working on next?

I’ve got books I’m developing, and a movie I sold to Amazon, and TV series I’m meeting on, and a graphic novel—and it’s always like that. I’m always setting boats in the water, I push them all in, and some of them get to the other side and some of them sink in the middle, and you just never know.

Interview condensed and minimally edited for clarity.