She grew up east of Troost before “east of Troost” became code for where Blacks were allowed to live in Kansas City. In her debut novel, East of Troost (She Writes Press, 2022), author Ellen Barker examines the upheaval and change her neighborhood experienced in the 1960s and 1970s as Black families were pushed east and white families fled west. The book’s white protagonist, following personal tragedy, buys her former family home and moves back to the neighborhood she grew up in, which is now predominantly Black.

Barker’s forthcoming book, Still Needs Work (She Writes Press, June 11, 2024), continues the narrator’s journey to rebuild her life and fit in with a new community on the familiar streets of her youth.

After graduating from Bishop Hogan High school in 1972, Barker moved to St. Louis to attend Washington University, where she earned a bachelor’s in urban studies. A career in urban planning, launched in St. Louis, has taken her to Massachusetts and California. She recently spoke with IN Kansas City by phone from her home in Los Altos, California, in the Bay Area, where she lives with her husband, Tom, and their German shepherd, Boris.

In the synopsis for your forthcoming book, Still Needs Work, the narrator, who was never named in East of Troost, is now “Marianne.”

[Laughs] You are a journalist. You’re the first person who’s picked that up. It’s the same person, but now we know what her name is.

That’s an interesting artistic choice. I take it to mean the protagonist, who is quite guarded, is slowly revealing herself to us.

That is true, she does. In the first book, all the looking back at the ’60s and ’70s, that was my life. So it felt weird giving myself a different name. In the new book it got too hard for her to be unnamed.

What street did you grow up on and on which block?

South Benton [Avenue] between 69th and 70th.

In East of Troost, the narrator recalls the riots that happened during Holy Week in 1968. How old were you then?

I was 14. At that age, it was very exciting and also terrifying. I was in 8th grade, and it was in the middle of the civil rights era, and we did a lot of social justice stuff in 7th and 8th grade.

What middle school or junior high did you attend?

I went to St. Louis Catholic School. It was 1st through 8th. That school was at 59th and Swope Parkway. It was farther north, so the racial transition was occurring there, and it was a very mixed school. There were Black and Hispanic and white students there. The Sisters of Charity were very liberal and social justice minded. We leafleted the Fair Housing Act, which was passed in 1968. We went door to door.

What are your memories of Holy Week 1968?

Martin Luther King had been killed [on April 4, the Thursday before Palm Sunday]. In a lot of places in America, schools were out the day of his funeral. That was five years after the Kennedy assassination, and everybody had off the day of Kennedy’s funeral. So the students wanted the school to be closed, and the Kansas City School District decided not to close.

Students at Southeast High School left school and marched down Swope Parkway and headed for downtown, which was a long way. So we looked out the window of our school and the street was full of kids marching north. In light of what we were learning, and the changes we were seeing in our neighborhoods—you’re holding two things in your head. One is, “This is scary.” The other is, “This is important.”

By the end of the day, the city had posted a curfew at dark, and there were rules like you couldn’t buy gas in a container, I think. In those days, there weren’t usually church services at night, but on Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday, there were. So that was a big thing—those services all had to be adjusted so everybody would be home before dark.

And then on television, you know, there are fires downtown and looting, so you’re thinking, “OK, burning things is wrong, looting things is wrong. But, you know, so is doing what we’ve been doing to these people. That’s wrong.” I never felt physically in danger, at that point. It was exciting. It was obviously a new thing going on.

What did your parents say when the riots were going on?

I don’t remember them discussing it with us. There was one television in the house that we all watched. We got two newspapers a day, the [Kansas City] Star and the [Kansas City] Times, and we all read those. The memory is gone of what we actually discussed, but there was no ranting and raving about, “This is terrible.” It did not incite racial hatred in the house.

Your book touches a lot on religion. You are Catholic and the neighborhood you grew up in was heavily Catholic. When the narrator in East of Troost moves back from California, she spends a lot of time visiting different Catholic churches and services to see which one she best “fits into.” She also muses with respect to taking time off from her remote job to attend a religious service that “any rumor of religiosity can be career-limiting.”

Yeah.

Was that more of a thing you noticed in California than when you worked in St. Louis?

Yeah, it was not a thing in St. Louis, or the 11 years that we lived in Massachusetts, which is also a very Catholic state. In California—and I was working there with people from all over the U.S.—people would spread rumors, like, “Oh, she’s a former nun.” [Laughs] They would just say weird stuff. I didn’t talk about it, ever. I would hear them talk about other people, too. It was usually when I was working in I.T., which is very male dominated, very alcohol soaked. My job was interfacing between marketing and I.T. so when I was on the marketing side, that was much more likely to be women, and they didn’t care, or they didn’t talk about it. It wasn’t an issue. But being with the I.T. people was a different thing. You have to watch everything you do.

In the book you also touch on the pressure in some work environments to engage in heavy drinking after hours to prove you are part of the team.

Yeah. The scene on a work trip to Australia where [the narrator] learns from a co-worker how to pretend to drink, that is a true story. I did learn that from a co-worker. She developed a reputation for being able to hold her liquor when she barely drinks at all.

So she’s not slurring her words because she’s not actually drinking.

Right, but they think she is, and they admire that.

It’s funny, when people think they are tolerant, and then turn out to have lurking intolerances, in this case, towards people who are religious or don’t drink.

Yes, exactly.

When was the last time you were in your old neighborhood and why?

Oh, I was there in September this past year. I was back for a wedding. Angie in the book (the narrator’s childhood best friend) is really named Tricie. She lived on Montgall, which is now gone in that part of the city.

Because it was in the path of Bruce R. Watkins Drive/ US-71.

Yes. Tricie lived near 70th and she still does, but over in Kansas now, in Prairie Village. Her son got married, so I was back for that. And I drove over to the old neighborhood a couple of times. Do you want to hear about it?

I do.

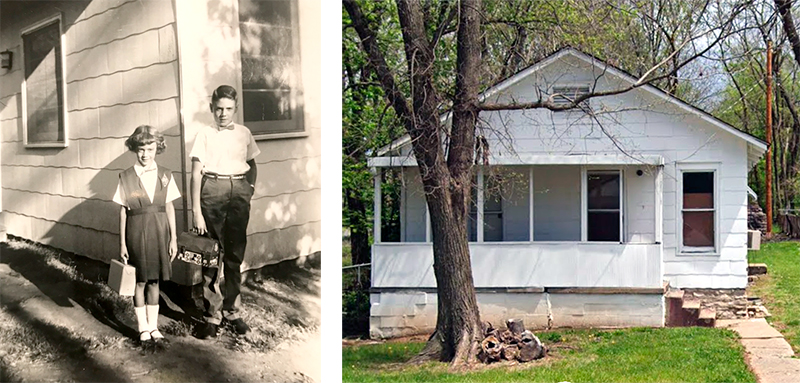

So, a year earlier, when East of Troost had come out, Tricie and I had gone over and looked in the windows, and by that time, the electricity was disconnected, the gas meter was gone, the windows were broken, there was a big dip in the roof. It was clearly going to be one of the many houses coming down.

Then I went back last fall, prepared for, you know, gone. And somebody was working on it!

Did you stop?

I did. Of course I did. I walked around, tried to look in the windows. Nobody was there. Nobody was living there. So I walked around the house and I heard this voice say, “Hey, are you the owner?” It was the guy across the street. And I said, “I used to live here, but I don’t now.”

So we talked about it. And it turns out he owns four houses across the street. He lives in one of them and rents the others. He’s been there since 1978. There was one family left from the time I was there, and he died last year. It was so interesting talking to him, and I gave him a book, of course.

Reading about the hardware store in the book made me want to shop there.

That hardware store is a real place. You can go there. It’s called Midland Hardware on Prospect at Gregory.

Is it still the same as when you went there as a kid?

Yup, it’s got the same floor even. Nick Gadino has owned it since 1976. Marianne spends a lot of time there in Still Needs Work.

The house itself seems to be a character in the novel. Was that your intention?

No, but it did turn out that way, didn’t it?

What made you start thinking about the role a physical house plays in our lives?

I think it was when I was in Kansas City for a high school reunion in 2017. I hadn’t been by the house in the intervening years after my parents moved away because if I was staying with a cousin or a brother or a friend, nobody would go over there. Nobody would go east of Troost—they’re “not going to the dark side.” But then I had a car so . . .

Did people actually say that, “the dark side?”

I had a cousin who said that. Yeah. So in 2017, I had a car, I was on my own. I knew the neighborhood wasn’t as bad as it was in the ’70s. The house had a blue tarp on the roof, and I could see in and see it was pretty much like it was when we had left.

Nobody’s living there, so there’s no knocking on the door and going in. And it was kind of heartbreaking. So I went home, and I would think about it periodically. I’d think about walking in that front door.

I think I conceived the idea that I could save the house in the novel even though it couldn’t be saved in reality. So Marianne, who didn’t have a name at the time, was my avatar. She went in to save the house.

It must be a joy, after writing the novel as an act of grieving in a way, to then go back and see that the house is not coming down after all.

That’s right. There is still a little bit of grieving, though, because it’s gutted. So there will never be a reason to go in and look at it. The kitchen has been ripped out. It needed to be—I’m not objecting to it—but it will not be the same house.

Interview condensed and minimally edited for clarity.