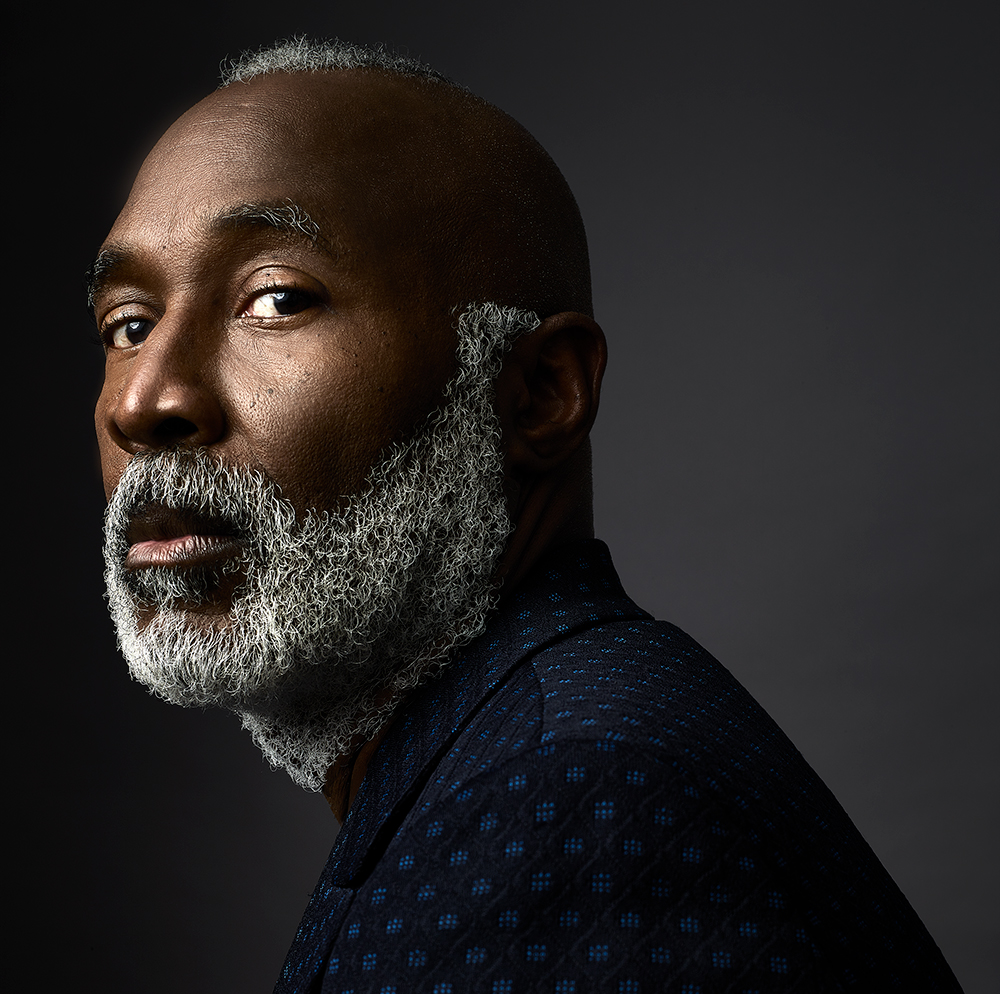

He speaks in hushed, soft tones punctuated with thoughtful pauses like the open spaces in his beaded artworks. For a lifelong Midwesterner, born and raised in Fulton, Missouri, and a longtime resident of Chicago, artist Nick Cave has a surprising Southern drawl (“still” becomes “steel”), so a recent, long phone conversation with IN Kansas City was marked by frequent silences, because you just want him to go on talking forever.

Cave, who earned his BFA at Kansas City Art Institute and MFA at Cranbrook Academy of Art, rocketed to international acclaim in 1992 with Soundsuits, created in response to the Rodney King beating at the hands of the Los Angeles police department. Soundsuits, wearable sculptures that produce sound with motion, provide protection and liberation by concealing race, gender, and class. Cave, 61, who trained as a dancer with Alvin Ailey, often performs in the Soundsuits, leading exuberant dances and parades on stages and in the streets.

Nick Cave: Until, on display through Jan. 3 at the Momentary in Bentonville, Arkansas, is the artist’s most ambitious project yet, spanning more than 24,000 square feet. The show was created in response to the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. As Covid-19 delayed the opening of the show from March until September, the George Floyd murder and Black Lives Matter protests erupted, charging the exhibition with renewed relevance.

The show’s immersive displays include Kinetic Spinner Forest, a roomful of backyard garden spinners where menace lurks beneath beauty and Crystal Cloudscape, a glittering raft containing ten miles of crystals and 24 chandeliers concealing a secret garden that can be viewed by climbing ladders that looks like aircraft passenger stairs. The show debuted at MASS MoCA before traveling to Sydney, Australia, and Glasgow, Scotland. The Momentary, a new art space in a former cheese factory, is its final stop; it is open Tuesdays through Sundays, closed Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day; admission is free; masks are required.

Cave’s recent artistic responses to the Black Lives Matter protests can be followed on the Jack Shainman Gallery website and on Facebook.

You got your BFA at the Kansas City Art Institute. If you were to create a Soundsuit or installation about Kansas City, what would that look like?

Well, I did that when I was a student there from 1979 to 1982. I galvanized a group of students and friends to create a processional performance down to the Plaza in garment constructions I created. I did this type of thing frequently. The biggest change in my work since then is that I now have the means to realize ideas in their fullest, without compromising.

I still have great connections in Kansas City with the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, with collectors such as Sharon and John Hoffman, and Christy and Bill Gautreaux, and amazing friends like Sean Kelly, Jim Hubbell, Howard Mitchem, Bruce Burstert, and Gregory D.—where are you? So, it holds a very special place in my heart.

What was your childhood like in Fulton, Missouri, and how did it shape you?

It was quite lovely. I was number three of seven brothers, and my mother was one of 16 children.

That makes me imagine fun family reunions.

Yes! And family holidays. My family has always been very close, very connected. I was surrounded by unconditional love and by creative people: quilters, woodworkers, seamstresses. My parents were very supportive, not that they really understood the arts, but I was always doing that sort of thing. My brother Jack, who is a year older, is an artist as well. We would set up still lifes and paint them, and we learned how to macrame. Even when I would be hanging out with my brothers, I was also always vicariously watching at a distance: “Oh, what is my grandmother making? What is my aunt making? She’s sewing on a sewing machine, what does that mean? What does that look like?”

We lived in an all-black neighborhood, so I didn’t have a sense of racial injustice early. I enjoyed that innocence of childhood, but my parents did sit my brothers and me down and explain to us about our identity and the obstacles that may come with that. It was definitely brought to our attention that our skin color is seen as a threat, but that it was not going to shape who we became.

Have you ever been stopped for jogging while Black or driving while Black or otherwise not breaking the law?

Oh, yes, a number of times. The first incident, I was just moving into my adulthood. After studying at KCAI and doing my masters at Cranbrook, I came to Chicago to live. I was walking home from teaching at the Art Institute of Chicago. I have my portfolio in hand, walking in the street. All of a sudden, I’m surrounded by, like ten undercover police cars, and they are like, “Lay down on the ground.” I was like, “What is going on?”

The convenience store down the street had been robbed. I mean, do I look like someone that could have…

Yes.

Right, obviously I looked to them like someone that could have done it—with portfolio in hand.

And we all know the reason why.

Right. And so, I followed all instructions. And then they realized they had the wrong person, and they basically all got in their cars and sped off. And there I was, standing there, in this sort of state of shock.

What was going through your head?

I was thinking, “Three seconds ago, my life was targeted. My identity was violated.”

Another time I was at the Shedd Aquarium with friends that were in town, and we were looking at the exhibitions. And all of a sudden, two undercover cops…throw…me…to…the…ground.

My friends just went ballistic. I went ballistic: “What the f**k is going on right now?” They said, “Sir, please be quiet.” You know, somebody is attacking me—how am I supposed to be quiet? They pull me into this room, and they say, “We had someone report that there was a black guy with a white T-shirt on and blue jeans that stole a purse.” And I was like, “OK. I didn’t do that.” Again.

And they were like, “We’re very sorry.” And I’m sitting there thinking, “Do I go report this, or do I not go report it? What good is it going to do if I do go report it? Are there going to be any repercussions from this act?”

Or, does pursuing it just set you up for more disrespect and prolong the trauma?

Right. And you’re just kind of stunned. For six months, I was so paranoid when I would see police. Literally paranoid.

Do those incidents still reverberate in your life?

Yes. When I go out at night, if I’m coming home at three in the morning, I’m thinking about my route. No side streets. It’s about being in a public atmosphere with lights. It’s about staying out of situations with police that could be altered to look very differently. It’s part of my existence that’s very real.

“…not only is it an exhibition about police brutality and social injustice, but it’s also a space for convening, for us to collectively come together and talk about racism in America. The project is kinetic, it’s immersive, it’s transformative. It speaks about optimism and hope, but yet it is burdened with all the disparity.”

So the title of your current exhibition, Until, is informed by your personal experience.

Yes, it refers to the notion of “innocent until proven guilty” or “guilty until proven innocent.” I was first invited to do a project for MASS MoCA in their Gallery 5 space, which is the size of a football field, in 2013. Denise Markonish, the curator, came to my studio and said, “I want you to think about what you want to do. I’m going to go away for a year and come back and see what you’ve come up with.” I continued working in my studio, not thinking about it at all, and [the] Michael Brown [shooting in Ferguson] happened. And I wondered, “Is there racism in heaven?” And all at once, the project became clear.

Did you ever imagine back then the events of this spring that would unfold as you were preparing to mount Until in Bentonville?

Oh my gosh, no. Until was supposed to have opened in April at the Momentary in Bentonville, but with Covid, it was pushed back. And when George Floyd happened [in May], it was like, “Arrrggh. We need Until out in the world right now.”

I am just thankful that it got up. Because not only is it an exhibition about police brutality and social injustice, but it’s also a space for convening, for us to collectively come together and talk about racism in America. The project is kinetic, it’s immersive, it’s transformative. It speaks about optimism and hope, but yet it is burdened with all the disparity.

Because for me, that’s how life is. The emotional trauma that I have to carry as a person of color is heavy, constantly compartmentalizing all these incidents in order to navigate and to function in this very treacherous country. You wonder why you’re not happy. Or why you’re feeling sad.

When George Floyd happened, all of a sudden, all those feelings I had been trying to suppress rose to the surface. And so, you know, it’s just a lot to juggle all at once. I’m fortunate to have art as a vehicle to pour all these emotions into. But it is tough. It is hard. It is unfortunate. And yet, I’m able to keep forging forward through art as a form of protest.

When you walked through the exhibition in Bentonville, in light of the events of this summer, were new aspects of meaning revealed, even though you created it?

Totally. The thing about this exhibition is, all the venues are very, very different. There’s a lot of renegotiating placement, renegotiating how people will move through the exhibition. It allows me to reimagine, reconfigure the experience differently. But the essence remains relevant. I think the most amazing thing was just feeling a sense of comfort and ease and reflectiveness. It settled me.

Sometimes it feels like racism and violence are woven into our society, like patterns in the Beaded Cliff Wall in your current exhibition. On the other hand, you get to work with students as a professor at the Art Institute of Chicago. Do they give you hope that a better future is possible?

Oh, totally. I think with the young generation, history is history—they are not living that history. The injustice, the brutality—they’re not standing for any of it. And they have come to be open to inclusion, diversity in a very, very different way than previous generations.

Your work has been described as having a quality of radical joy. Do you feel at this moment like radical joy has a chance against the darkness?

Yes. I guess I can only sort of hope for that. I think we’re in a very critical time right now: We’ve got to collectively decide: How do we want to live? What kind of America are we? What kind of America do we want to become?

Interview condensed and minimally edited for clarity.