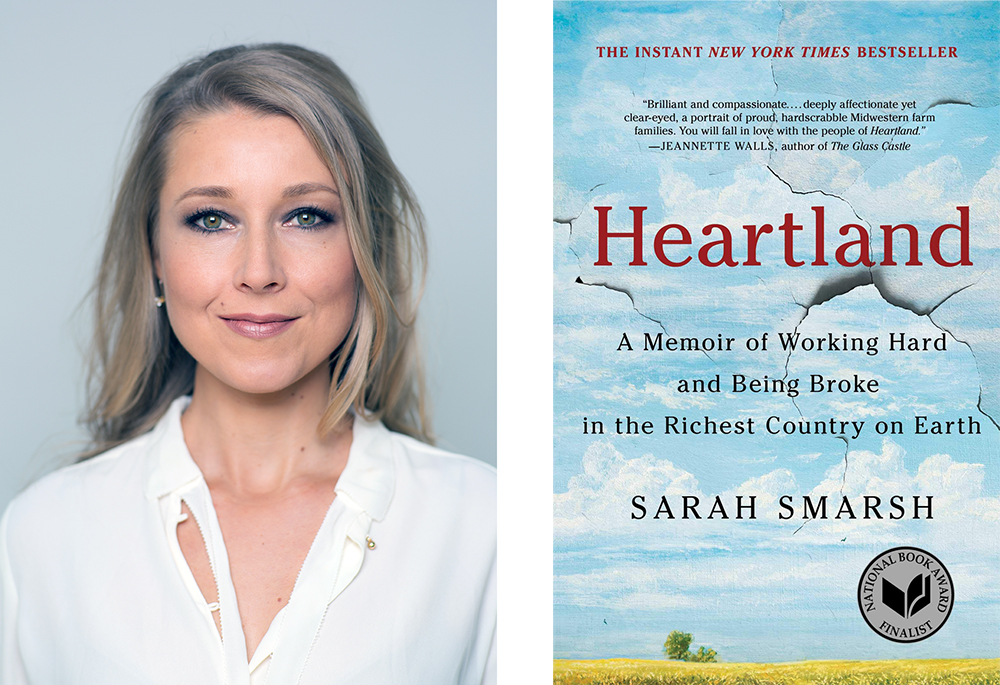

Lithe and blond with wide gray-green eyes and high-heeled boots, Sarah Smarsh could easily be mistaken for someone that “never had to lift a finger,” as her grandmother would say. But looks are deceiving. The 39-year-old native of Kingman, Kansas, on the dusty plains west of Wichita, is tough as a square nail, forged by the grinding physical labor and constant high-alert mode that is the birthright of the working poor.

She was born a fifth-generation Kansas wheat farmer on her paternal side and the daughter of generations of teen mothers on her maternal side. Her Facebook profile picture is of her as a girl hauling a sack of feed over her shoulder.

The first in her family to go to college, Smarsh earned a master’s in nonfiction writing from Columbia University as well as journalism and English degrees from the University of Kansas. She has written about socioeconomic class, politics, and public policy for the New York Times, the Guardian, and other newspapers.

Last year, Smarsh’s book Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth (Scribner, 2018) became an instant bestseller and was honored as a National Book Award finalist. It has just been released in paperback.

Heartland is an unsparing account of life for poor working whites in the Midwest, a group that remains largely invisible to outsiders. In college when Smarsh described her childhood on the family farm, people reacted with shock and said they had never heard of such an existence outside of The Grapes of Wrath.

But Smarsh’s hardscrabble youth didn’t crush her spirit or dilute her love of Kansas. In her book she writes, “The place we lived was full of sharp objects, poisons, and frustrations, but there were moments—maybe most moments, on the whole—like in Dad’s truck with the windows down, when the west wind that reached us all the way from the Rockies cleared the air, and I felt more free than I’ve ever felt in cleaner, safer places.”

Smarsh, who lives in Kansas, spoke at length by phone with IN Kansas City shortly after wrapping production on a new six-episode podcast series called The Homecomers about rural America that will be out soon.

In Heartland you write about your very private decision not to have children yet, but you don’t reveal much about your romantic relationships. How did you set boundaries of what to share and what to shield in your memoir?

It actually took me a long time to find that boundary. If I had set out to write that list of my own personal biggest troubles, the hardest moments, and perhaps even the most salacious details of my family, it would have been a very different book.

So it wasn’t that I just wanted to confess a bunch about my life and then found a theme and tacked it on. It really flowed in the opposite direction. I wanted to say something about class in America and that was the guiding force as to what was or was not important. Some of those details were very intimate and uncomfortable to share. I’m a very private person by nature and so that was a real act of faith, I guess, in the reader to respect me along the way.

You write a lot about your grandparents in the book. Can you identify one trait from each of them that you feel you either inherited or aspire to?

When I was a little kid, I used to tell Betty, my maternal grandmother, who I think of in many ways as the star of the book, “Someday I’m going to write a book about you.”

Somehow I knew decades ago I was going to write this book. The best that I could understand it when I was a kid was that it was somehow about her, and of course it ended up being about generations of my family, and it centers on my internal life.

But I researched her life specifically and interviewed her for many years to offer her life as a microcosm of the ultimate toll of poverty and specifically of being a poor woman—a price that she paid in many ways much more excruciatingly than I did. She has been a hero to me for her tenacity and her resilience.

I think I did inherit the tenacity part and the resilience part. The part that I aspire to—and I think she is absolutely golden in this way—is her generosity. By that I mean not just sharing when she’s able or giving when she can, but the unconditional love and forgiveness and compassion that she brings to every human interaction. I witnessed that when I was a kid and she was a parole officer talking to very hardened guys with criminal backgrounds. She’s incredibly decent and humble, regardless of who she is around or that person’s background or class or color.

As far as my grandpa Arnie, I would say his humor is something that I would aspire to. The life of a writer—you know [big sigh], making sense of these big issues—can feel like a very serious pursuit. My grandpa Arnie was someone who every day did backbreaking physical labor and never once complained and was every day smiling and laughing and finding joy in the world around him.

It’s been said that for many people born into poverty, no matter how well they do later in life, they can never change the internal image of themselves as being poor. Do similar feelings ever sneak up on you?

I might be overstepping with this statement, but I think it’s true: I no longer carry that syndrome of poverty with me. Over the years, I have gotten over the most difficult neuroses or internal struggles that I carried with me that were shaped by poverty.

That said, I carry with me what W.E.B. Dubois called a double consciousness.

In what way?

I’m always aware, if I’m in a middle- or upper-middle-class space, of the contrast between that world and the place that I come from. I think that’s a healthy awareness. It’s not a sense of shame about where I come from and it’s not a sense of guilt about being in a more comfortable place, but it’s rather just an acknowledgment that there is a vast space between my direct, lived understanding of the world growing up and the world that I now operate in professionally.

Can you give an example of how that comes up?

Maybe I will hear someone make a joke that my senses can recognize as classist, but that that person’s blind spot about class allows them to make. My being present in that space allows me to raise my hand and say, “People where I come from don’t usually end up in a room like this, but here I am, and so allow me to explain to you why that remark is insensitive and inappropriate.”

I look at that straddling of two worlds as a gift in some ways.

Your book challenges the American idea that everyone is responsible for their own success or failure. What is the problem with the pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps mindset?

When I was a teenager and a very young adult, I often felt very alone in my ambitions and goals, because they were so different from the place I came from. No one around me had any sort of road map to tell me how to get there.

But the older I get, I see that I did not do it alone and no one does. Yes, I worked hard. I did a lot of things that in a better-off household would have fallen to the parents. I had to grow up fast.

But, when I was a first-generation college student, there was a federally funded program called the McNair Scholars that encouraged me to apply for graduate school, which I probably never would have done. I didn’t even understand the difference between undergrad and graduate when I was a straight-A college student.

We think of class as income but it is so much more. It’s vocabulary and information and social capital and networks. McNair Scholars’ encouragement and their paying for my application fees to the Ivy League university I ended up getting into changed the trajectory of my life. I brushed up against an opportunity that my brilliant grandmother or mother or father didn’t have.

We have to have the humility to recognize that whatever good outcomes we have in our lives are a result of a mixture of our individual skill, talent and hard work and circumstances beyond our control. All you have to do to know that that’s a fact is look at good, decent, hardworking people like my family who have worked their asses off their whole lives and have very little to show for it if anything at all, in material terms.

So that story that we tell—that all it takes is hard work—is a myth, and it benefits people in power.

We’ve been having a national conversation about race and the idea that white people have privileges they may be unaware of. Do people also have class privileges that they are unaware of?

Oh absolutely, yes. It’s sort of our foundational myth.

The myth that we don’t have a class system.

Exactly. My very first story that I had picked up by the Associated Press almost 20 years ago was about class.

It’s only been in the last few years that the country is ready to talk about it. Because we are so nascent in that conversation, there is an immense blind spot. That blind spot exists at all rungs of the class ladder, but it is most dangerous in boardrooms and the halls of government.

“So that story that we tell—that all it takes is hard work—is a myth, and it benefits people in power.”

Why?

Because even if people in power are well-intentioned, if they don’t recognize the continuum of inequality which absolutely intersects with race and gender, we can hardly rectify a problem which hasn’t been named.

What is your assessment of the current political climate in Kansas compared to other places?

In Kansas, many of us here on the ground are witness to what I would call a burgeoning progressive populism. That certainly is happening nationally, but I think there is a special signature to it in this region. The Midwest has a deep history of the left-leaning form of populism that has been percolating and growing nationally. It tends to not get as much coverage as right-wing populism, but it’s there.

I see it as a course correction for a country that has, in my mind, been moving dangerously to the right for several decades. We saw a moderate or centrist side of that in the midterm election in Kansas when we elected Laura Kelly and sent Sharice Davids to Congress. I think that trend will continue.

What do you think about concerns within the Democratic Party that there is a danger in moving too far to the left?

You know, I think that we can have both moderate and progressive liberal thought in this country simultaneously [laughs], and it’s healthy.

I personally bristle at any assertion that proposed changes are too radical if those changes simply seek to ensure that all Americans have health care and a livable wage and are treated respectfully.

I find that those who chasten the most boldly progressive platform and who seek incremental change tend to be folks who are doing OK. If you are suffering at the hands of an inaccessible health care system or an unfair economy, it doesn’t feel like you have time to wait.

Considering how much your life has changed, do you think you could ever live in Kingman, Kansas, again? Could the person you are today fit into that community?

Oh, yes, absolutely. I happily choose to live in Kansas, which is the state-level answer to your question, even though most of my professional work is based in New York City. I am in the mix every day with the family members I wrote about in the book. Working class and working poor Kansas communities are what made me and who I belong to. I never sought to get out, and in many ways, I’ve chosen not to. So the short answer to your question is yes [laughs]. m

Interview condensed and minimally edited for clarity.