The boundary waters between reality and fiction are where Kansas City’s homegrown, celebrated novelist Whitney Terrell feels most comfortable plying his literary craft. Terrell, 54, began his career in journalism, doing a stint as an intern at the Kansas City Star and landing a job as a fact checker for the New York Observer.

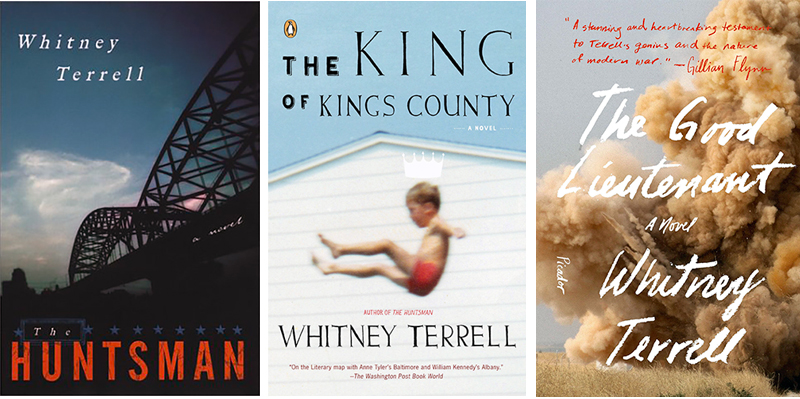

But fame came from his debut novel, The Huntsman, in 2001, an unblinking look at the racism lurking below the surface of elite Kansas City society, a world Terrell was born into. In 2006, The King of Kings County, a fictionalized account of the racial covenants used by J.C. Nichols to segregate the city’s close-in suburbs, was named a best book of the year by the Christian Science Monitor and landed Terrell on a list of top writers under age 40 by the National Book Critics Circle. In 2016, his third novel, The Good Lieutenant, about the Iraq war, made best-book lists at the Washington Post and the Boston Globe.

Terrell is an associate professor of creative writing at University of Missouri-Kansas City. He is working on a novel tentatively titled Home, which is set in Kansas City during the Obama and Trump administrations.

Terrell chatted with IN Kansas City by phone from France, where he was vacationing with his wife, Gayle Levy, and their sons Morrison (Moss), 17, and Miles, 12. He discussed his critiques of his hometown, why America keeps getting sucked into endless wars and what he thinks the Democratic Party could be doing better.

Why did you and your family pick France for a vacation?

We’re here because my wife is a French professor at UMKC, and UMKC runs a study abroad program for students from all around the country to study the Resistance in France [during the German occupation of the country in World War II]. Lyon was a hub of the resistance, so we’re in Lyon. We’ve been here as a family at least six summers. We usually stay for all of June and half of July.

What do your kids enjoy doing in France?

They both went to Académie Lafayette (in Kansas City) for their early schooling, so they learned French, and we put them in French school when we get here. So, they go to class.

Miles plays a lot of pick-up soccer near our apartment, and Moss is really into theater, so he spent a couple of weeks in Paris recently. He stayed with a friend and went to see a bunch of theater.

Your first two novels were very critical of Kansas City, particularly the elite old guard of the city. Why do you choose to continue to live here?

[Laughs] Being critical of a place does not mean you don’t love it. Criticism and discussion and feeling like you are participating in creating the narrative of a city is a kind of investment. I only have that investment in Kansas City.

I feel invested in working with others to think about the way that narratives have been told incorrectly or unfairly and trying to create narratives that are more fair or more accurate. As a writer, I feel that is my best material—the place that I feel most connected to and that I care about the most.

In both The Huntsman and particularly The King of Kings County, there are lovely descriptions of places such as the colonnaded apartment buildings along Armour Boulevard, the Country Club Plaza, and Mission Hills. Do you struggle personally with how much it’s OK to feel nostalgia and affection for some places where segregation and racial covenants played a role in their formation?

I would say that’s true of the Plaza. The apartments on Armour Boulevard were from a prior period. I don’t personally feel a tremendous amount of nostalgia for the Plaza. I like downtown. I’ve been excited about downtown’s renaissance. I like the sort of weirder parts of the city. I like the West Bottoms. I like the East Side, where I live. I think Columbus Park is interesting.

Would you say your feelings about the Plaza are tainted by what you know about J.C. Nichols and his racial covenants?

Yeah, for sure. That changes the legacy of the Plaza radically for me.

Social ostracization is a theme that emerges in your early books. Did you ever feel ostracized as a result of the critiques in your books?

No. I come from a position of real privilege in this society, from a family that’s lived here a long time. Very rarely do people do anything that is negative. Sometimes they do, but compared to the historical issues we are talking about, and the way that people have been marginalized in this city, particularly people of color, nothing has happened to me that’s worth really mentioning.

You covered the Iraq War as a reporter and as a novelist. Does each of those forms require a different mindset and is it hard to shift from one to the other?

Yeah! Writing The Good Lieutenant—I’m very proud of that novel…

Why?

I think it succeeds in the way I wanted it to succeed. But, it took eight years to write. It was very hard to do. The journalism I wrote came immediately. It was easier to process and tell the story in a nonfiction way.

Why is that?

When you’re doing nonfiction, you have control over the plot. It was hard to avoid telling a traditional war story, which is: Young man goes to war, trains, faces combat, determines whether he is a quote-unquote man, and wins the medals or dies.

Sounds vaguely familiar.

That arc of so many movies including Top Gun and Star Wars, which says that combat teaches you whether you are a man, is not true of combat. Combat is very bad for people, destabilizing, debilitating, traumatic. It changes people’s lives and doesn’t teach anyone anything about whether they are a good person or not. It’s too random.

Also, my character in The Good Lieutenant is female, so she’s not trying to find out whether she’s a man. So, to find a structure that wasn’t doing that was hard. The story is told in reverse chronological order to avoid putting combat in a privileged place in the narrative.

Your podcast fiction/non/fiction covers the intersection of literature and the news. Do you observe any blurring of the boundaries between fiction and news, and do you have concerns about trends in either category?

No. I think it’s very important for fiction writers to be familiar with writing nonfiction. At UMKC we have a multi-disciplinary program, so you can study creative nonfiction and fiction or poetry or screenwriting or playwriting in the MFA program. I don’t think I would have been able to write The Good Lieutenant if I didn’t also know how to write journalism, because there were no embedded novelists in Iraq.

Maybe that’s a bad thing.

Maybe it is, but it wasn’t happening. So, I had to go and write nonfiction about it. I also knew I was going to write a novel.

Journalism has been crucial in all my books. In The Huntsman there are scenes set at the Kansas City Star that were based on my internship there as a reporter just out of college. There are ideas in the book that come from news stories that other people at the Star wrote. I’m constantly looking into newspaper archives for ideas for stories and to research stuff.

The Huntsman came out 20 years ago. Do you think we have made any progress in that time in overcoming racism?

The phrase “overcoming racism” is too broad to say “yes” to, right? No, we have not overcome racism. We have evidence of [racism] that happens every single day in America. Kansas City specifically feels like a more diverse city now than it was in the ’90s. And I don’t mean just in terms of black and white. There are more diverse kinds of people living in Kansas City, from more diverse backgrounds than there were 20 years ago.

Troost Avenue is no longer a completely solid dividing line between black and white. I live a couple of blocks from Troost. I used to live on the east side of Troost, and I still own a house there. I know what the neighborhoods are like. They are fairly integrated. If you go over The Paseo or Prospect, that is not a very integrated space, but I think those lines are changing.

Another difference is that a lot more white students are going to public school in Missouri than were 20 years ago. Now, that mostly is in charter schools, and you can debate whether or not that’s a good thing, but it is a difference. My kids’ school, Académie Lafayette, was not perfectly integrated, but it was integrated.

If you look at the political leadership of the city, it’s been much more diverse also.

The King of Kings County came out in 2005, one year after Thomas Frank’s What’s the Matter With Kansas. Frank grew up in Mission Hills and is just two years older than you. Both your books take a hard look at class divisions, something no one was really talking about at the time. Do you know Frank, and do you consider yourself a populist, a word often used to describe Frank’s writings?

Yeah! In fact, I just had Tom on the most recent episode of the fiction/non/fiction podcast. He was here in France and came to visit me in Lyon, and we did the show together with my co-host, V.V. Ganeshananthan.

What was the topic?

What the Democrats should do now that the Supreme Court seems to have turned so far right.

What should they do?

We were arguing that what they don’t talk about is winning votes in the Midwest and South. Missouri used to be a bellwether state that voted for [the winner of] the presidency, whether it was a Democrat or Republican. We only vote Republican [for president] now. You can win votes in Missouri as a Democrat, but the Democratic Party is not trying. That is very frustrating to me.

The Good Lieutenant is a searing criticism of the Iraq War. Since it was published in 2016, do you see any shifts in American attitudes toward endless wars overseas?

Absolutely. President Trump, who I do not like and did not vote for, campaigned openly against the war in Iraq and Afghanistan. That would have been unthinkable for a Republican politician during the Bush era, right? So, the Republicans have abandoned those wars and certainly the Democrats have as well. Joe Biden received a lot of criticism for leaving and ending the war in Afghanistan. But that was the right thing to do. You don’t see some sort of policy disaster happening now because of that departure.

So, I do think Americans will for a short period of time be uninterested in doing war, and then the old war narratives will come back, and we will drum up and try to have another one, and we’ll have to argue. It’s always about narrative. When you start seeing movies that are pro-Iraq War…

Watch out.

Right. It was interesting to me what preceded the Iraq War. There was a resurgence in interest in the quote-unquote Greatest Generation. There was this tremendous amount of interest in World War II and how wonderful and fantastic it was for us to fight in those wars and win them. That narrative was part of what made it possible for Bush to invade Iraq.

When you see your own kids and the students you teach, despite all the challenges their generation faces, what gives you the most hope?

I feel like my kids have grown up in an environment that is more diverse, more accepting of people of different sexual orientation and different ways of thinking about gender, and they are not caught up in the sort of culture-war arguments that were taking place when I was in high school. I am hoping that is going to be a trend for the future.

Interview condensed and minimally edited for clarity.