Of the 600 letters Darryl Burton wrote from jail, one would free him from his wrongful murder sentence. Another would free his soul.

‘‘I’m glad to be here,” Darryl Burton begins his presentation at Leawood’s Church of the Resurrection. “But then, after what I’ve been through, I’m glad to be anywhere.” He delivers the line with the smooth timing of a seasoned public speaker as the audience chuckles.

The laughter stops as he continues his story that could be a movie script. With passion and sincerity, the man behind the pulpit shares vivid details of rage and injustice, violence, and fear.

Like many good movies, this one has a happy ending. Fifteen minutes after he starts speaking, the crowd rises as one to applaud the man who served 24 years in prison for a murder he didn’t commit.

At age 22, Darryl Burton was enrolled in college with a vow to give his 7-month-old daughter a better life than he’d had. The middle child of nine, he’d been raised by his mother and grandmother. His parents had divorced, and he rarely saw his father.

Those dreams of a future were dashed when he was arrested for shooting a drug dealer not far from his mother’s house in Ferguson, Missouri. There was no evidence—only the testimony of two men who said they’d seen Burton at the scene. Burton met with his court-appointed defense lawyer once. The jury took just one hour to deliver a guilty verdict and Burton was sentenced to 50 years without parole plus 25 years.

“I was filled with rage,” Burton remembers of those first days of incarceration in Missouri State Penitentiary, called the bloodiest 47-acres in America for its brutality. “I hated everyone; the men who’d lied on the stand, the judge, the corrupt prosecutors, and my public defender.”

But Burton channeled that rage into the goal of getting released. He spent hours in the law library, learning a new language of legalese and writing letters to individuals and groups, from senators, presidents, and congressional leaders to newspapers, television stations, and Oprah Winfrey.

But there was one letter that changed his life. “My mother and grandmother were very religious,” he says, “but when I was a teen, I told my grandmother I no longer wanted to go to church. She said, ‘Someday, Darryl, you’ll need Jesus Christ. And I hope you remember to call on Him.’”

Ten years after incarceration he recalled his grandmother’s words and wrote this letter.

Dear Jesus Christ,

If you’re real, then you know like I know I’m innocent. So, if you help me get out of this place, not only will I serve you, but I’ll tell the world about you.

Sincerely, Darryl Burton

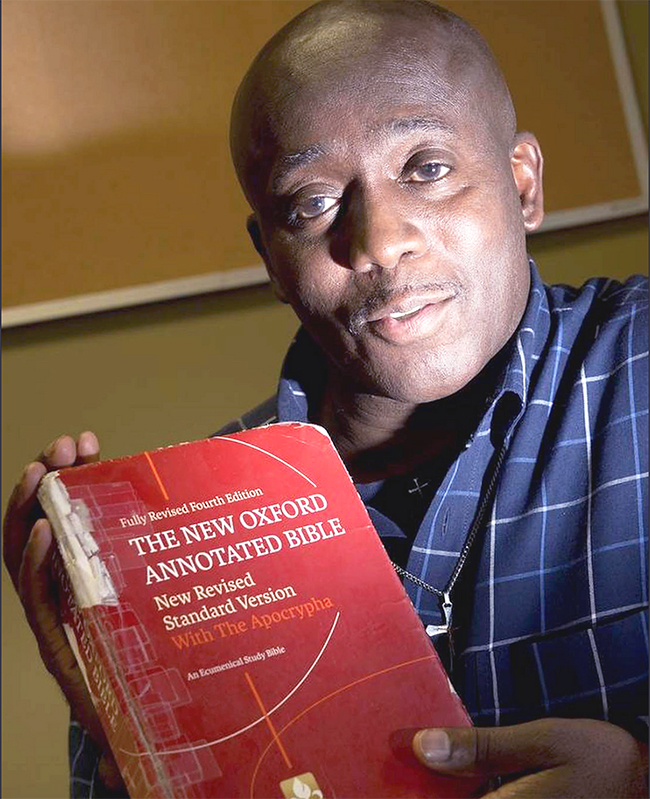

He reread the letter often; at the same time, he began reading the New Testament. One teaching was hard to accept. “Jesus said we must forgive our enemies. And at first, I grudgingly forgave them through clenched teeth. Little by little, I released that hatred, and it freed my heart.”

His fellow inmates and even guards noticed changes in Darryl. He was calm, even smiling, despite his situation. “I was no longer in prison emotionally,” he recalls. “I’d found peace.”

Now he had to obtain his physical freedom. An inmate told him about Cheryl Pilate, a Kansas City-based lawyer who’d helped wrongly accused men and women go free through Centurion Ministries in Princeton, NJ. This national nonprofit, founded by James McCloskey in 1980, has freed 63 men and women serving life or death sentences for crimes they did not commit.

Cheryl Pilate accepted Burton’s collect call and asked him to send a letter detailing his circumstances. While the team at Centurion agreed he had a viable argument, their backlog of clients meant it could be ten years before they could take on his case. Burton continued to write letters to the group, urging them not to forget him. In all, it was nearly a two-decade-long process that would lead to his exoneration.

The Wrong Man

Burton was teased as a kid for his ebony complexion. “I was darker than my siblings and school mates. They called me ‘Light’s Out’ and worse,” he recalls. Now the childhood embarrassment would become a blessing.

Centurion investigators located the gas station attendant who’d witnessed the crime decades before. The witness described a man who had light-to-medium colored skin. “You have the wrong man,” she would tell anyone who listened, but her testimony wasn’t allowed at the initial trial.

Centurion brought the woman to Missouri to testify on his behalf. “It was a miracle,” Burton says, “that after all these years she was still alive and willing to help right this wrong.” Based on her accounting and other findings by the legal team, Burton was exonerated in 2004.

He remembers his release on August 29, 2008, as surreal. “When the warden told me I was getting out, I didn’t believe him. I’d had so many dead ends before and experienced defeat after defeat,” he said.

But this time it was true. “Within a few minutes,” Burton says, “it seemed like the whole prison knew I was being released. I remember standing in the control center in front of a plate-glass window overlooking the floors of jail cells. The guards must have opened them because inmates were out there, cheering, waving, thumping their chests, giving me signs of prayers.

“It was like I was in a trance,” he recalls as he walked through the last two doors leading to freedom. “Later I was told I began chanting, ‘praise God’ over and over.”

If time stood still during his years in prison, the outside world had continued to evolve. He experienced the first of many changes—from subtle to significant—as his legal team drove him to his mother’s house, seat belts, speed limits, cell phones.

That Friday afternoon the small group stopped at a TGIF restaurant to celebrate. “When I learned the name stood for Thank God it’s Friday, I thought it was a good sign.”

As he sat in the booth, overwhelmed by the vast menu, Cheryl Pilate asked what he wanted for his first restaurant meal after more than two decades. Steak? A hamburger? Barbecue? A beer? Burton ordered a salad.

As a vegetarian, in jail that meant a wedge of iceberg lettuce with no dressing. Now it was a luxury to be served a plate piled high with greens and vegetables with ranch dressing. And when he took his first bite of a mozzarella stick, he wondered out loud who would ever think about deep frying cheese. He might just learn to like this new world.

Starting Over

The legal world had dealt Burton an unfair sentence, and now—even after his release, it worked against him. Because his exoneration wasn’t based on DNA evidence, he wasn’t due compensation for his time in jail. That meant he was released with no money, no promise of a job, no training. He was on his own.

It would take him two years to find a paying job. He’d been volunteering at Catholic Charities, a group that helps people start over with housing and resources. “I was sweeping floors, cleaning up, anything I could do,” he says. Then the organization created a new position for him. As a re-entry coordinator, Burton helped others navigate the difficulties of life outside of prison.

“One of the first obstacles is getting valid identification,” he says. “A social-security card, a driver’s license. The first steps to a new life.”

Burton realizes he’s one of the lucky ones. The United States has one of the world’s highest recidivism rates. According to a 2021 report by the Harvard Political Review, 76.6 percent of inmates are rearrested within five years of release.

To help others get out and stay out of jail, Burton founded Miracle of Innocence (miracleofinnocence.org) with Lamonte McIntyre, a man who was exonerated in 2017 after serving 23 years for a crime he didn’t commit. The organization assists with legal resources, exoneree care including housing, transportation, job training, and physical and mental health needs.

“Our aim is to educate communities about injustice and to help innocent prisoners not just gain release but reenter life outside of jail successfully,” said Burton.

He brings up Kevin Stickland, whose story is getting ample coverage in the news. “If he gets out—and he should—after 40 years, the world is going to be all new to him. He will have a network of people ready to help, including Miracle of Innocence.”

Promises Kept

Some people pray for a miracle and once it happens, they forget any promises they made to a higher power. Burton made good on his vow to tell the world about Jesus the day after his release.

That first evening at his mother’s house was overwhelming as he was surrounded by family members and friends he hadn’t seen in decades. By the next day, he knew he had to get away. Away from the noise, the excitement, away from the city that meant unfairness to him.

He hitched a ride to Columbia, Missouri, with a pastor he’d met in prison. When asked to tell his story in front of his friend’s congregation, he found his voice.

Since then, Burton has honed his delivery. He speaks with eloquence and humility, sometimes adding humor as a break from the horrors he’s seen. He speaks in front of civic organizations and legal groups, in biker bars and massive auditoriums around the world. His message is one of hope and forgiveness. At one Olathe high school, he described how telling untruths can have life-changing consequences.

Now he has an official pulpit. In May, 2016, Burton graduated from Saint Paul School of Theology in Kansas. He is now an associate pastor at The United Methodist Church of the Resurrection in Leawood. Karen Lampe, the church’s former executive pastor of congregational care, calls him an amazing gift. “I think he wants to make up for lost time,” she says.

Family Man

Burton now feels blessed in ways he could not have considered possible two decades ago.

He has reunited with the daughter he left when she was just an infant, and is married to Valerie, a woman he praises for her compassion and joy. “I’ve never met anyone with such a happy spirit,” he says. Theirs is a blended family with his daughter and three from her first marriage. They have nine grandchildren.

His blessings continue. Along with his pastorship at Church of the Resurrection, volunteer work at Catholic Charities and the Don Bosco Charter High School, and busy speaking schedule, Burton is writing an autobiography (find out more at darrylburton.org). And if his life story seems like a movie script, he’s already received inquiries about making a film.