Just one “look.”

That’s all it took for Kansas City fashion designers to strut their stuff down the world’s runway.

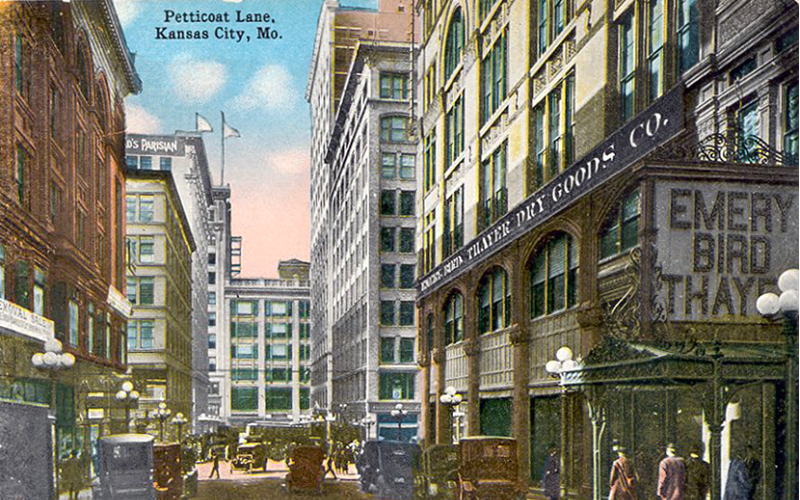

You can see many of these “looks” at the Historic Garment District Museum, open by appointment, at 801 Broadway Boulevard, says Denise Morrison, the director of collections and curatorial affairs. “The Historic Garment District, between Sixth and Eleventh Streets, Washington and Wyandotte, was the hub of Kansas City fashion,” she says, from the 1920s to the 1980s. “From 1940 to 1950, one in seven American women owned a garment made in Kansas City.”

The museum was cofounded in 2002 by designer Ann Brownfield and Harvey Fried, a champion for downtown revitalization and the son of a dress manufacturer. Brownfield left an oral history, on video, in the Garment District Oral History Collection through the Kansas City Library.

From yesterday. . .

At the turn of the century, the port of Galveston, Texas, was the gateway through which Eastern European immigrants, many of them skilled seamstresses and tailors, made their way to Kansas City to start their own businesses and thrived. Yet the demand for skilled seamstresses continued to outpace supply. Soon clothing manufacturers devised the “section” system, by which each worker would only make one section of a garment, over and over.

By World War I, Kansas City manufacturing grew as companies from the East Coast moved West for lower taxes and wage rates. Many shops employed immigrants from Italy and elsewhere. Again, business thrived.

During World War II, Kansas City companies made underwear and uniforms for the Army and Navy.

‘‘Kansas City, in the last century, had 150 companies employing 8,000 people. It was a wonderful ecosystem of wholesalers, retailers, manufacturing, and sales reps to really make it a success.”

– Jennifer Lipka

“Kansas City, in the last century, had 150 companies employing 8,000 people. It was a wonderful ecosystem of wholesalers, retailers, manufacturing, sales reps to really make it a success,” says Jennifer Lipka, the director and founder of Rightfully Sewn, a nonprofit training a new generation of seamstresses. “It wasn’t unusual to see racks of clothes being pushed down the sidewalks to be packed and shipped all over the country.”

Kansas City became known for everyday wear.

Blue jeans. For Lee Jeans, making overalls and work clothing for ranch hands in the early 1900s morphed into jeans that every cowboy wore in every Western that hit the big screen. Lee also hit a cultural nerve in 1947 when they made blue jeans for women. French fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent once confessed that he regretted that he had not invented blue jeans. “They have expression, modesty, sex appeal, simplicity,” he said. “All I hope for in my clothes.”

By 1966, Lee Jeans was successful enough to build the “tulip” building at State Line Road and Shawnee Mission Parkway for their national headquarters. It’s now the 1900 Building, where the banquettes in the celebrated restaurant are upholstered in denim, a nod to the past.

Housedresses. If you were a housewife in the early part of the 20th century, you wore a housedress at home to go about your wifely chores. This humble garment got a refresh from Nell Quinlan Donnelly Reed with ruffles and aprons and other dressmaker details. Just because the garment was utilitarian didn’t mean that it couldn’t also be pretty. Plenty of housewives agreed.

Nelly Don, the label she founded, made over 75 million dresses from 1916 to 1978, making it the largest dress manufacturer of the 20th century.

Sailor dresses.When the late political consultant Steve Glorioso was a teenager in the early 60s, he worked as a packer in his father Joe Glorioso’s company Krest Originals, a popular dress line. “My dad would say, ‘take them to Harzfeld’s or Adler’s,’” popular Kansas City stores, he recalled. Sales reps would also take them around the country to smaller stores in the rural Midwest. Joe Glorioso, a Sicilian immigrant, had trained at the Kansas City Art Institute and would go to New York to sketch the fashions he saw along Fifth Avenue. “His biggest seller was a sailor dress,” Glorioso remembered, which the company would modify for Midwestern customers.

Junior Coats and Dresses. Harvey Fried, cofounder of the museum, worked for his father as well at the Fried-Siegel Co., which made junior coats and dresses.

Warm-Up Suits. In the 1960s, Brownfield created couture as well as ready-to-wear, and everything from shoes to coats to junior dresses and the warm-ups for the 1972 U.S. Olympic ski team in Sapporo, Japan. For the Kansas City label Brand & Puritz, she designed 250 coats each season. She would travel around the country to talk to store buyers about what was selling. “We were still big time,” she says.

But a series of upheavals in the 1960s spelled the end for the Garment District. Mechanized farming meant fewer workers, thus a decreased need for work clothing, a staple of Kansas City’s trade. Newly formed chain retailers crowded out the smaller apparel shops and many unique Kansas City dress and coat labels. And workers who might have trained to be seamstresses learned to do something else.

By 1982, the Garment District was closed for business. Much of this fashion history still needs to be saved, says Morrison.

As designers knew then, with their sailor dresses and cowboy jeans—the key is to tap into the spirit of the times.

To Today. . .

In the 1970s, the dollar was strong, airline fares were cheap, and a new generation of Americans were rediscovering the allure of travel.

Alpaca Styles from Peru. One such intrepid adventurer was Annie Hurlbut of Tonganoxie, Kansas. Studying anthropology at Yale University, Hurlbut went to Peru to work on an archaeological dig. There, she encountered the alpaca, the pack animal of the Andes, valued for its extraordinary wool, which naturally ranges from creamy white to brown. “In 1976, I went to Peru to study the market women of Cuzco,” she recalls. Their hand-loomed alpaca garments were warm and practical, but not stylish, so Hurlbut turned designer. She asked the women to make garments from her designs, and started Peruvian Connection with her mother, Biddy, as a partner.

In 1979, Hurlbut brought an alpaca flight jacket and a boot-top sweater with a fur-trimmed hem to show to buyers in New York City. Luxury store Bendel’s promptly gave her a sizable order for more. And the new design business was off and running.

Today, Annie Hurlbut Zander lives in Kansas City, while the headquarters remain on the old family farm in Tonganoxie. Peruvian Connection has an online catalog at Peruvian Connection—the most recent one photographed in the Flint Hills—and an international clientele, including stores in Santa Fe, Aspen, Washington, D.C, Kansas City, Chicago, and London. Those first trips to Peru yielded much more than alpaca garments, says Zander, it yielded “a lifelong fascination with the Andean textiles, precious alpaca fiber, handcrafted goods, Peru’s people and traditions, the enchanting landscape.”

That fascination has now also manifested in designs for the home—table linens, wallpaper, bedding, and more—all with Peruvian Connection’s distinctive colorations and the look of timeless, time-worn places.

New and Vintage Kimono-Inspired Designs. Elizabeth Wilson developed a deep interest in Asian art and culture, nurtured by living in San Francisco. A trip to Japan in 1969 cemented that fascination. But what to do with that passion? At an early stage in her career, Wilson described herself as “an itinerant disseminator of Chinese art history” at San Francisco State, University of California-Davis, UMKC, and KU. Wilson met and married Marc Wilson, former director and CEO of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

In 1977, Elizabeth Wilson and Fifi White opened an antique shop on Westport Road. Wilson also started buying antique and vintage kimonos at auctions in Japan. “Kimono at that time cost a couple of dollars each. I kept buying more,” Wilson says. Over the years, she has purchased over 10,000 kimonos. Some became part of Asiatica’s prized collection, some went to museums, others have been exhibited at galleries (such as the Dolphin in 2009) or recycled into modern garments. Around 1980 White suggested, “Let’s make clothes.”

“It was a very successful antique business,” says Wilson, “but the transition to clothing gave us a much broader audience and a national audience. It soon became the tail that wagged the dog.”

Kimonos are constructed of 12-inch-wide lengths of fabric—cotton, linen, and silk—so the clothing designs started with that framework. Says Asiatica’s designer Kate McConnell, whose background is in textile design and fine art, “Our fashions are timelessly chic, and we make everything here. Elizabeth buys the fabric, either kimono or new fabric from Japanese makers. We then decide how we’re going to use it.” Today, “modern, one-of-a-kind pieces” are Asiatica’s calling card at their shop in Westwood, online catalog, and trunk shows around the country.

Red Carpet Ready. Graphic designer and longtime seamstress Sarah Nelsen spent six years at Asiatica before launching her own design house in 2017 emphasizing “luxurious minimalism,” she says. In her studio in the Livestock Exchange Building in the Stockyards, she specializes in “couture pieces, gowns for special events, and ready-to-wear made to order,” she explains.

Nelsen favors a sleek, elegant, metallic, and less-is-more glamorous style. She dressed blues singer Danielle Nicole for the 2019 Grammys when Nicole was nominated for “Best Contemporary Blues Album.” Says Nelsen, “When I was creating Nicole’s custom look for the Grammys, I had her Spotify station streaming on repeat. Art inspiring art.” Nelson has also dressed the folk/pop trio Olivia Fox.

Nelson does everything in-house, from patternmaking, cutting, fitting, sewing, and creating the catalog. “I do this because it brings me joy,” she says.

Fresh Prince Ready. When designer [and 2022 IN Kansas City magazine Innovator & Influencer] Whitney Manney got the call from the costume department of Peacock streaming’s Bel-Air, a TV remake of Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, she was ready. A graduate of the Kansas City Art Institute and self-taught seamstress, Manney had just the colorful, fluid, urban-inspired streetwear that the show was seeking. It didn’t hurt, either, that one of the show’s creators was Kansas City native Morgan Cooper.

“Creating clothes can be like creating a world,” says Manney. From jackets and handbags in her favorite denim to her signature “drippy” earrings in colorful enamel, Manney’s work is on display on her website. Manney aspires to be the next Betsy Johnson, Kimora Lee Simmons, and Donatella Versace all rolled into one. Starting her business in Kansas City has been a plus, because “the city gives us the space to create at our own pace,” she says. “In a fashion city, you’ll be a dime a dozen. Here you can afford a studio.”

‘‘….the city gives us the space to create at our own pace. In a fashion city, you’ll be a dime a dozen. Here you can afford a studio.” -Whitney Manney

And Tomorrow. . .

The fashion merchandising and design classes at Johnson County Community College continually attract new crops of fresh creatives with a vision, who then receive essential instruction in patternmaking, cutting, draping, and sewing. The late Mary Ellen Rixey, a Nelly Don model for years, recently bequeathed her extensive collection of period clothing that was housed in her Fairway attic to JCCC, so students can study garment construction and styles from the past.

And there might even be a new Garment District on the horizon. Says Lapka, “Kansas City is a wonderful breeding ground for creativity. The Stockyards area is poised to be the new fashion district.”

Fashionistas don’t have to travel to either coast to have a signature look. “Kansas City’s identity is changing from flyover to fly-to,” says Nelsen.